Developing soccer skills: moving with the ball

When to do it, what parts of the foot to use and how underloads aid attackers’ dribbling development. Moritz Kossmann explains all to Steph Fairbairn

"We all universally come to the game of soccer because we love playing with the ball,” says Moritz Kossman.

“We all want to touch the ball and there’s a certain magic to that. That magic needs to be encouraged at every level.

"I think moving with the ball is the most basic and pure form of that.”

Moritz is a coach at Ubuntu Football Academy in Cape Town, where he coaches the U21s, who play in the third tier of South African football, and oversees the senior section, made up of U18s and U16s.

He lends his expertise on moving with the ball, covering what it is, the techniques and the building blocks for players learning the skill…

SCW: What are the main differences between running with the ball and dribbling?

MK: When I, as a player, have the ball on the field, you could refer to any action - while I still have the ball - as ’protecting the ball’.

But running with the ball would be in situations where there is less, or no, opponent pressure.

An example of that would be a central defender receiving the ball and they have a large amount of space in front of them, because the opponent is playing in a low or mid-block or something like that.

They might want to carry the ball towards that block to provoke pressure. This we could refer to as ’running with the ball’.

When most people imagine dribbling, it has got a characteristic of a slalom action to it, where you might be trying to go around or through the gaps of several opponents - and it involves more changes of direction.

Running with the ball might happen more in straight lines because I actually want to cover a larger amount of ground in a shorter time, whereas dribbling has a more, perhaps, evasive aspect to it.

SCW: What are the techniques needed for running with the ball and for dribbling?

MK: Any person can run faster without the ball at their feet. So if I’m trying to run with the ball and cover a large amount of ground against little opponent pressure, I’m going to take less touches on the ball.

I’m going to push the ball ahead of me and attempt to run quite quickly behind it, in order to cover a large amount of ground in a short time. Whereas, if I’m trying to evade and beat opponents, I’m going to take many touches because I’m going to have to change direction. I’m also going to have to react quickly to attempts to win the ball off me.

The higher frequency of touches makes it much more possible to change direction, rather than if I’m running with the ball and just attempting to cover ground very quickly.

Then, I need a lower frequency of touches, because, naturally, I can run faster without the ball at my foot.

SCW: What parts of the foot might we use in different scenarios? What are some of the advantages of different parts of the foot?

MK: The basis for me would be to use the outside of the foot for running-with-the-ball actions, because, when we think of a natural running position, carrying the ball on the outside makes it possible to be more agile.

[It is] closer to a natural running position than when I’m dribbling it with the instep.

Dribbling it with the instep also has advantages. [Barcelona and Spain legend] Andrés Iniesta has a signature move, which they call La Croqueta in Spain, which is where he moves into the gap between two players by passing the ball from one instep to the other, thereby having a change of direction - from right to left, and then from left to right - very quickly.

This gives him the ability to go around the player or even to go through the gap of two players and have two evasive actions instead of one in a very short time.

If you look at a player like Lionel Messi, having a very high frequency of outside foot touches is his most prevalent way of doing it.

Then there’s also the possibility to dribble with the sole of your foot, which can be useful, particularly for turns, because it provides a high amount of control and the ball is trapped and a little bit more static under your foot.

You have got a high amount of control like that because you are also touching the ball with a larger surface area, and are able to touch it for a longer period of time.

There are moments where that can be extremely useful, perhaps for other actions where you are more front-on and not wanting to change direction 180 degrees.

SCW: How important is it that we encourage our players to develop their skills with both feet?

MK: I think it’s crucial. We are talking about an attacking action, which, both individually and collectively, are naturally more effective when they are less predictable.

Take a simple 1v1 as a starting point. If you are the defender and I am the attacker, and you know I’m right-footed, it’s possible for you to close the left side, make play predictable towards the right side, and have a better chance of winning the ball off me.

But if I’m proficient on both sides, then it’s much harder to guide me to a weaker side. It certainly contributes to attacking efficiency.

It also means I am more able to react to different moments that the unpredictable game of football might throw at me.

"If we are learn to use the outside of the foot, we have four parts to use in any moment..."

I think it is also crucial to learn to use different sides of the foot, especially the outside of the foot and the instep.

If we are able to learn to use the outside of the foot, then we have got two parts of either foot - four in total - to use in any moment.

That can help with disguise, but it can also help me develop a larger array of actions. Again, it just adds to the unpredictability.

SCW: Give us the building blocks as we go through the stages of beginner, intermediate and advanced. What might we be looking to coach players on when it comes to moving with the ball?

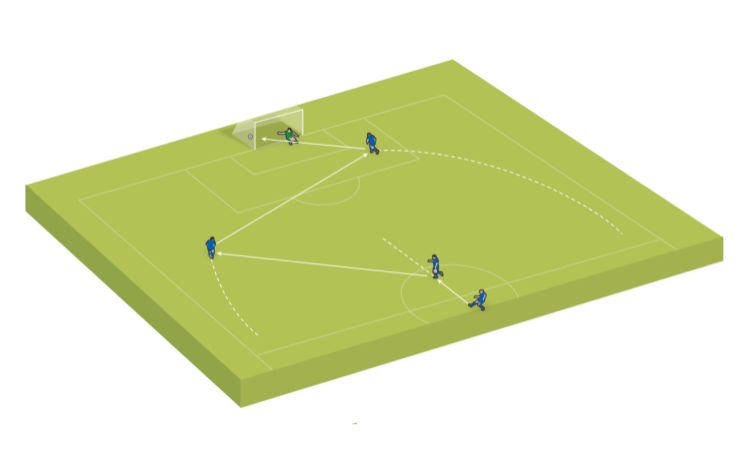

MK: The first aspect is just to get basic fundamental control of the ball. That, with most people, will require you to still look at the ball a lot.

The second stage is to use different parts of your foot to control the ball while doing this - outside of the foot, inside of the foot, sole of the foot.

Then looking up or away from the ball while moving with it is a massive key [element] that should come as early as is possible.

The next consideration is to be able to understand, in the context of the game, the role that passing and dribbling have; how, if no-one is in a better position than I am, I should be able to carry the ball; and the different types of dribbling for different game situations.

Related Files

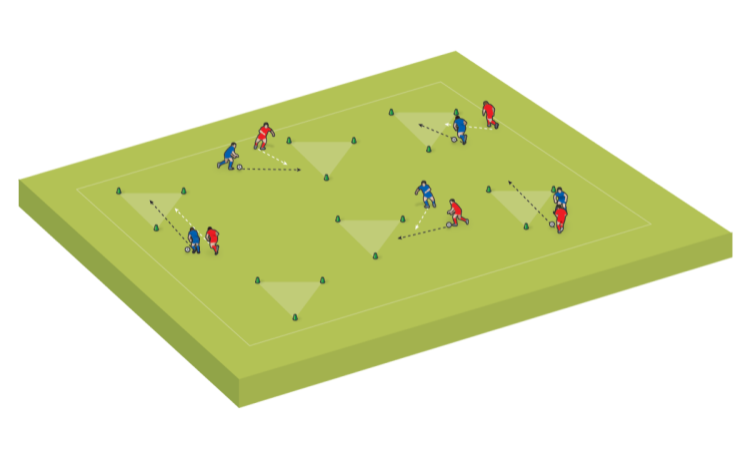

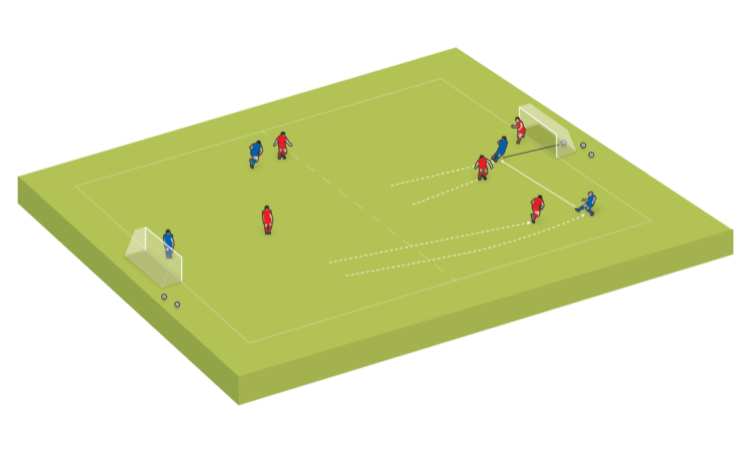

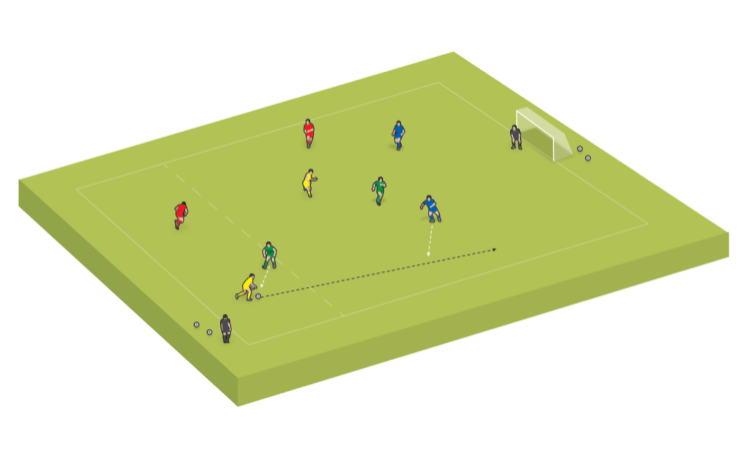

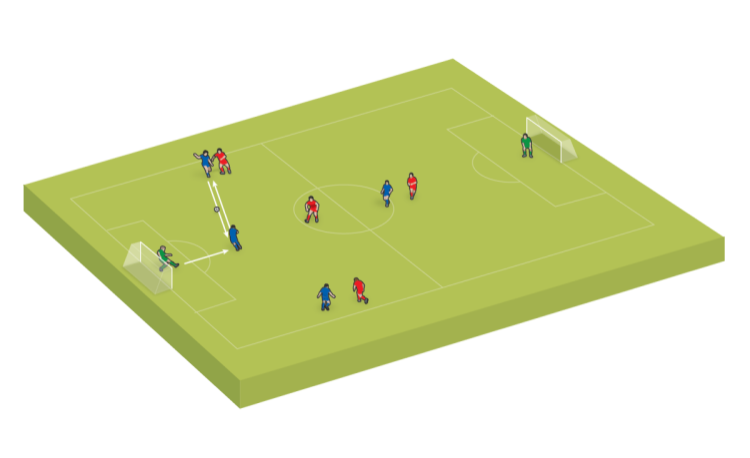

Perhaps a final stage, and that might mostly be for attackers, is to practice dribbling in underload.

If we look at any football team, they usually set up in a way that you have more defenders on the field than attackers.

When I am working in the final third, I won’t always have a clean 3v2 or 1v1 attacking situation. I might, more often than not, face underload attacking situations - for example, a 3v5, where three attackers are attempting to create a scoring chance against five defenders.

That is something we need to learn, because these situations happen frequently in 11v11, and so we need to prepare our attacking players to be able to still carry the ball and beat several defenders in a relatively small area.

That is a part of developing these kinds of players that make a massive difference to the game - creative, difference-making players, the Mbappés and Messis of this world.

But in order to produce more Mbappés and Messis, we have also got to train situations that these guys face very often in the game. I think that is where the underload attacking aspect comes in.

SCW: What final thoughts do you have for coaches on moving with the ball and dribbling?

MK: As the modern game evolves, passing, passing and more passing has become such an in-fashion thing – Barcelona is perhaps the most famous of the tiki taka possession-style teams.

But we need to understand that even those teams, at their most effective and their most efficient, had players who were able to beat opponents in dribbles and in difficult situations.

I would encourage our coaches not to over-restrict our players, especially with touch restrictions.

Don’t play two-touch every day. Don’t play three-touch maximum every day. Allow players to understand the game and allow them to dribble.

There is a place for touch restriction and we want our players to be able to pass.

But dribbling and passing are fundamental football actions. Let’s not over-restrict our players and create a generation that can’t give us these moments we all really want.

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Discover the simple way to become a more effective, more successful soccer coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Soccer Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use soccer drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of soccer coaching since we launched in 2007, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.