Why developing trust and a rapport with players is important

In the final article of his three-part series on best practice in coaching, James Mayley turns his attention to the details behind the building of relationships

The relationship a player has with their coach is one of the key determinants of the sustained engagement and development in soccer.

The coach-athlete relationship can not only impact a player’s motivation to train and play, but also moderate how players respond to feedback, setbacks and many other aspects of their football experience.

Coaching is an ever-evolving interactive process. Regular interactions take place between a coach and his or her players, and between the players themselves.

Relationships therefore form the bedrock of all coaching behaviours and constantly influence - as well as being influenced by - these ongoing interactions.

A statement we often hear as coaches is "you need to understand your players". However, it should be noted we are coaching people first, and players second.

All players have lives, families and experiences away from sport. Their experiences, values and challenges outside of soccer cannot be separated from their interactions and performances within the football environment.

Therefore, "you need to understand the people you coach" might be a better mantra to live by, as it recognises players as holistic human beings.

"Coaching is an evolving, interactive process. Relationships form the bedrock..."

One method coaches can employ to help build an understanding of players is inspired by influential basketball coach John Wooden, who kept information cards on all the players he coached, which he would frequently refer back to in order to guide his interactions with them.

The information he gathered related to both their wants and needs as an athlete, as well as their life outside of sport including family, background, academic studies and upbringing.

These documents can constantly evolve each time you discover something important about a person you coach. This could be in relation to what makes them tick on the pitch or a key piece of information about their personal life you can ask about at a later date, to show that you listen to and value them as a human being.

Relationships with the people you coach go far beyond understanding them and their needs.

Research into coach-athlete relationships found that mutual trust, respect, belief, support, closeness, cooperation, communication, and understanding are among the most important components that contribute to performance success and satisfaction. Let’s look at these various factors in a little more detail.

Mutual trust can only be developed over time. Consistency of message and coach behaviours form important parts of building this trust.

There are strong links between trust and the now prominent concept of psychological safety. This term refers to whether players view environments as safe for interpersonal risk-taking, such as asking for support, suggesting ideas and taking calculated on-pitch gambles.

To build trust, coaches should ensure their words are always reflected in their actions. For example, if you want players to be brave and creative on the pitch, and these risks don’t pay off, then the process - rather than poor outcome - should be what is focused upon.

This can be easier said than done if the risks end up in a negative outcome on the pitch, so coaches should constantly reflect on their values and ensure emotions do not overrule these in the heat of the moment.

In psychologically safe environments, the relationship and dialogue between coach and athlete always runs both ways.

Players should feel their views and needs are listened to and valued by the coach. For this reason, trust is closely linked to the concept of communication.

Regular, clear and consistent communication with players forms a vital part of the trust-building process. A coach’s communication style should also be adapted to meet the needs and, where appropriate, preferences of the athlete.

Moreover, regular communication with players is vital to ensure that the closeness of the relationship is maintained.

Coaches should also try to facilitate communication between players. Perceptions and feelings towards both the coach and other players are in a near constant state of flux and are likely to fade without continued effort on behalf of the coach.

Communication should also ensure that players are clear on their role within the team.

Role clarity is vital for players to feel settled and can prevent uncertainty or resentment towards the coach impacting their development.

When a player’s role within the team doesn’t meet their expectations or wants, then clear justifications for why and areas to work on to enhance their role can help maintain a player’s trust in the coach and perceptions that the coach is committed to their development.

Like trust, respect must be developed over time. It is important to acknowledge that respect needs to be earned and is given by players, not demanded by coaches.

Despite the need to build strong professional and often personal relationships with players, there is an almost imaginary line which should never be crossed.

This line is not always clear and is likely different for everyone. As a coach, it is our responsibility to set this and ensure it is not crossed so that respect is maintained.

Support can be considered both in relation to emotional and pastoral support as well as a player’s belief that the coach has the ability to improve their performance.

"Clear and consistent communication forms a vital part of the trust-building process..."

I have heard the line "connection before correction" at numerous coach development and CPD events. However, this overlooks the fact that the "correction" - in terms of demonstrating the expertise necessary to support a player’s development - is a vital part of building the connection.

Even the most likeable coach will struggle to maintain the trust of the people he or she coaches if they do not have faith in his or her ability to guide their development.

Finally, the idea of cooperation is closely related to horizontal or shared models of leadership.

While traditional soccer leadership follows a top-down approach - with the coach, or coaches, often sole decision-makers - lessons can be learned from the leadership approach of the New Zealand rugby union team.

Under the ’All Blacks’ dual-management model, a group of players took ownership over decisions on areas such as training design and matchday gameplans, operating alongside the coaches.

Such an approach not only helps cultivate positive relationships between coaches and players, but can also lead to innovative ideas from the playing group, as well as giving them a chance to develop their leadership, decision-making and game understanding.

KEY TAKEAWAY

Building, and maintaining, a positive coach-athlete relationship is a complex and ongoing task.

It takes constant commitment and vigilance on behalf of the coach, as well as the player, as the coach-athlete relationship is in a constant state of flux.

Taking time to understand players, and maintaining a record of this information, is a vital component of the relationship-building process.

However, coaches should also work to ensure that mutual trust, respect, belief, support, closeness, cooperation, communication, and understanding are maintained through their interactions with players.

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Discover the simple way to become a more effective, more successful soccer coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

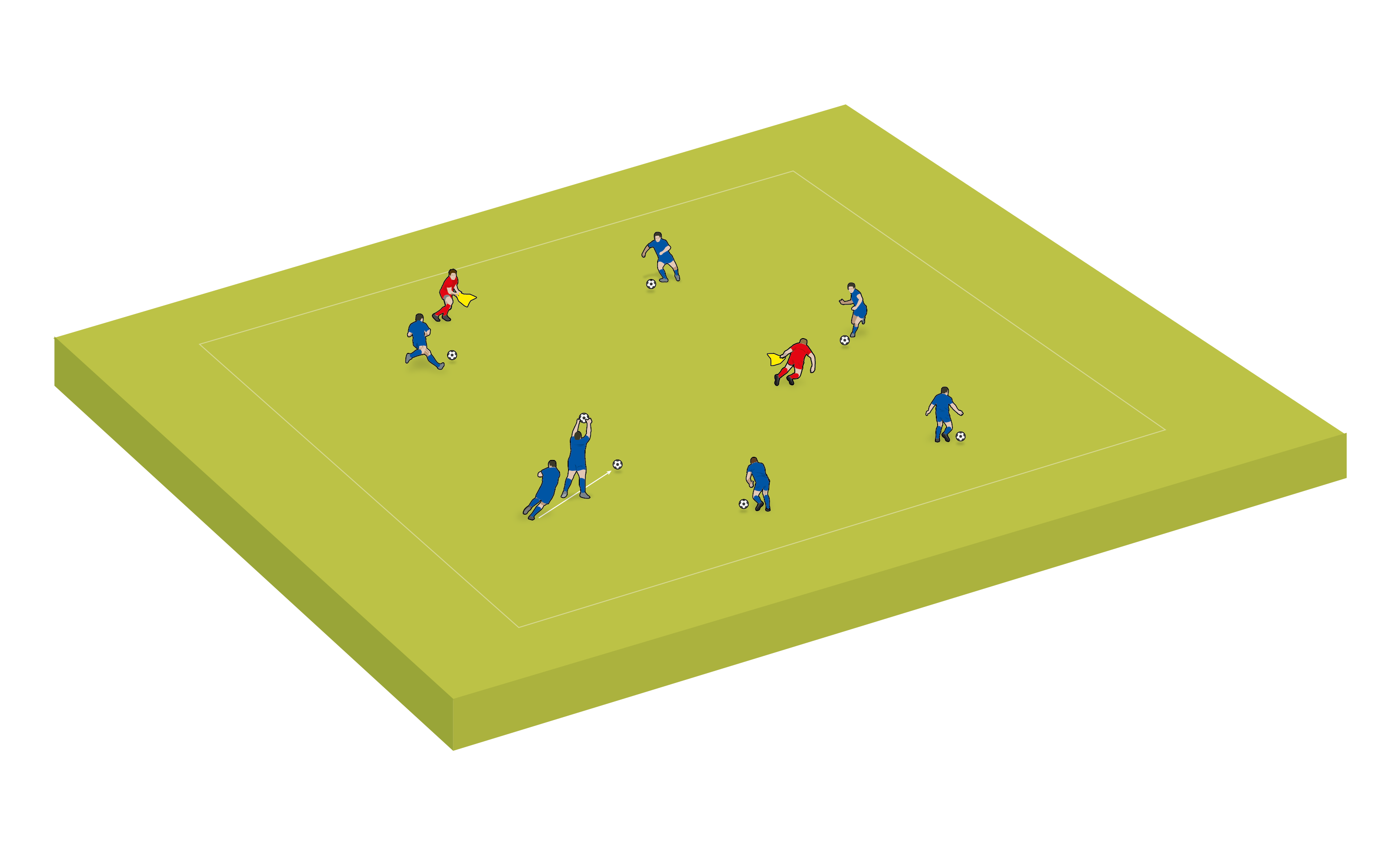

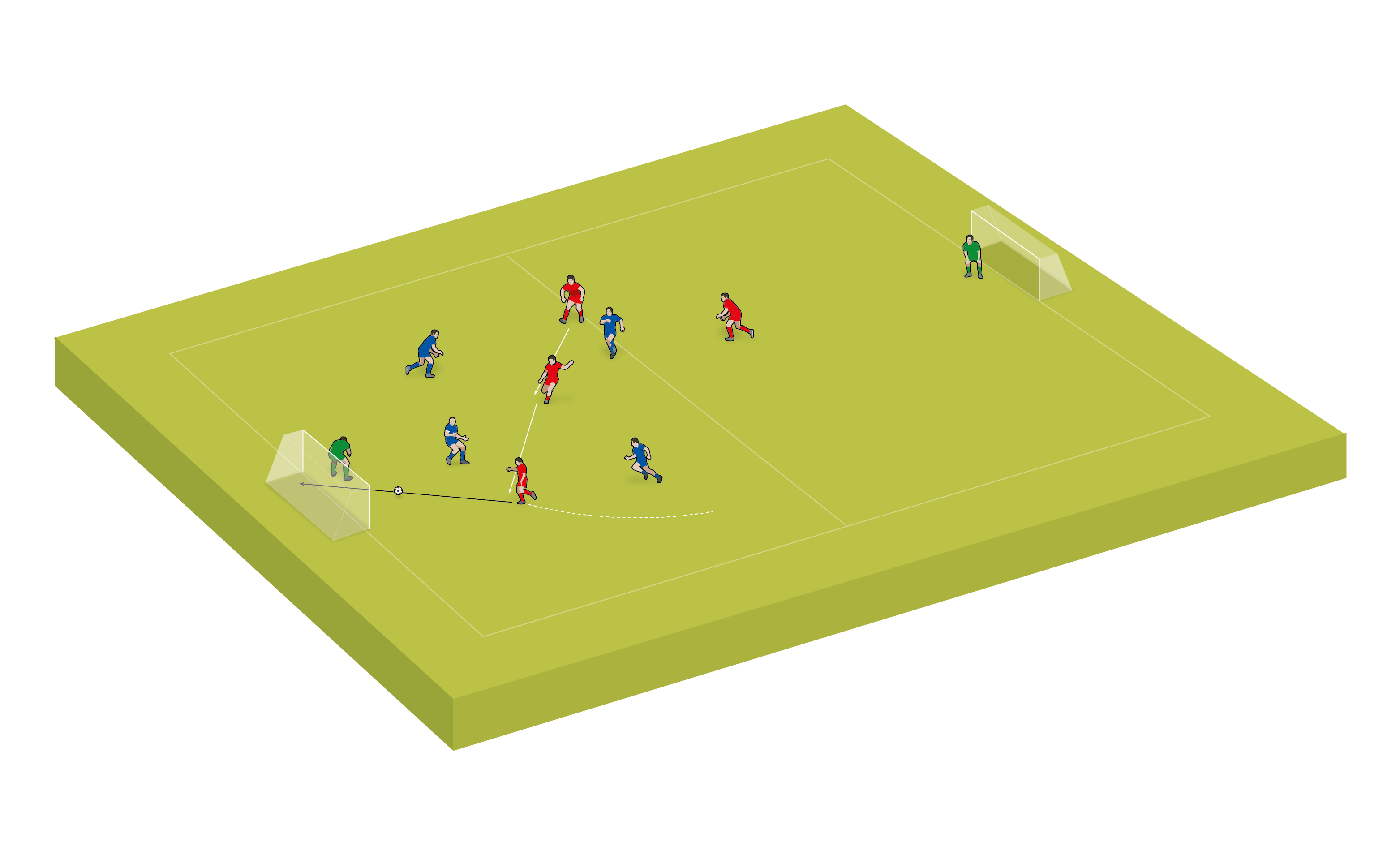

Soccer Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use soccer drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of soccer coaching since we launched in 2007, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.