Soccer's Principles of Play

Coaching Adviceby Peter Prickett

An extract from Peter Prickett's latest book Soccer's Principles of Play. In this part of the book Peter explores positive and negative transition and counter attacking and counter pressing as principles of play

This is an extract from Peter Prickett's latest book Soccer's Principles of Play. In this part of the book Peter explores positive and negative transition and counter attacking and counter pressing as principles of play

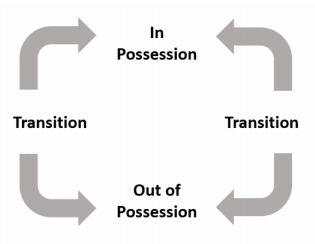

Transition

Compared to the other principles of play, the term transition is a relatively new addition. It is most often used to describe the moment (or moments) when a turnover in possession occurs. Transition is not a passage of play that teams will seek to create, but it is a passage that teams will seek to exploit or control. It can be seen as a moment to win or lose, and many coaches believe that if you win the transitions, you will win the game. Transition has been sub-categorised into positive and negative phases within the game cycle. Whether the turnover is characterised as positive or negative will depend on whether a team has just regained or lost possession.

Positive Transition

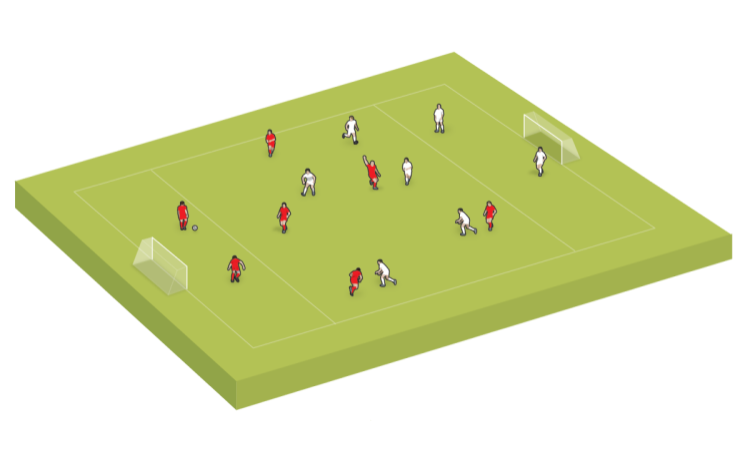

The objective of positive transition (or regaining possession) will generally be to attack as quickly as possible. This is connected to the in-possession principle of penetration/go forward. Teams who have turned over possession will be lacking in defensive balance and have left spaces to be exploited. When this situation has been established, in-possession principles come into play.

In essence, a race is formed between the team who experienced positive transition and the team who experienced negative transition to get organised and appropriately positioned (with in-possession and out-of-possession principles being applied at amplified speed). Can the counter-attacking team create an opportunity to score before the recovering defensive team can get into a position with suitable depth, cover, and balance? When the out-of-possession team has recovered and achieved balance, the counter-attack is over, and the game resumes at normal speed. Teams are coached into how positive transitions should unfold. The most common of these apply to the speed of the attack, where the transition has occurred, and the player who has regained possession.

As the counter-attack is reliant on rapid attacking, time limits or a specific numbers of passes can be applied to guide the action. At one time, England youth teams used a 6-6-6 rule.

• Can the team attack with at least six players?

• Can the team progress into the opposition half in six passes or fewer?

• Can the team regain-possession within six seconds of losing it?

The first two rules encouraged fast attacking and for players to get forward in support of the players in attack. Unsurprisingly, a player who attempts to counterattack alone is unlikely to be successful.

As a strategy, teams will focus their regaining of possession in specific areas. Any such strategy will also relate to negative transition, but the objective of negative transition may be to create a positive transition as quickly as possible. Should a team aim to regain the ball close to the opposition goal, different support will be required, and different passes will be required (in comparison to regaining possession close to a team’s own goal). The spaces available to exploit will also differ. The status of a player regaining the ball will also impact the possibilities of counter-attacking. If a player has just made a tackle to regain the ball, that player is possibly poorly positioned to attack themselves. The player is also likely to have been focused on the ball and have a poor awareness of the situation on the pitch. Many coaches encourage this player to quickly play a short pass to a teammate.

Example

A decade ago, the Manchester United forward line of Rooney, Ronaldo, and Tevez punished the opposition with counter-attacks. Ronaldo possessed exceptional pace, and whilst Rooney or Tevez were not especially rapid sprinters, both could move quickly enough, more important to their success was their speed of thought and recognition of space. The team most famously destroyed Arsenal in the Champions League in 2008/9, and one play from that match stands out where, holding a comfortable lead, a sweeping move sealed the victory.

In the 60th minute, Arsenal delivered a corner from their right-hand side. A defensive header cleared the ball to Ronaldo approximately 10 metres outside the United penalty area. From Ronaldo’s lay off, a pass was punched out by Park Jisung to United’s left side, and Rooney took the ball and ran at the defence. Moments later, he fizzed a low pass across the Arsenal box to Ronaldo who fired home. The move was over in four passes and five seconds!

Negative transition

Should a team turnover possession, they experience negative transition. Whilst the terminology of positive and negative are the (currently) favoured descriptions, they quite literally carry positive and negative connotations that may not be accurate. Fundamentally, any team that loses possession will seek to regain possession at some point. If their priority is to regain possession as quickly as possible, they will pressure aggressively. If their priority is not to concede, they will prioritise organising themselves into a balanced structure. The 6-6-6 rule referenced above suggests that players attempt to regain the ball for six seconds after losing possession.

Barcelona under Guardiola had a similar rule, and many teams have used variations on a five- or six-second rule. When that time is up, players no longer pressure to regain the ball – they drop into organised defensive positions. The idea of counter-pressing has gained popularity and become particularly associated with German football. A counter-pressing team aims to win the negative transition, using it as an opportunity to launch a counter-attack.

Countering the counter is potentially even more devastating as a team transitions from being out-of-possession, into being in possession, and will then have to transition once again to being out-of-possession, all in an incredibly short time frame. The defensive structure and balance will be weaker and exploitable.

Example

Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona side employed a five-second rule to regain possession after a turnover. Training sessions were developed specifically to improve the players’ reactions to losing possession. At RB Leipzig, meanwhile, Ralf Ragnick used a metronome, ticking down the seconds within which players had to regain possession.

Calculated pressing became popular after AC Milan’s success in the late 1980s and early 1990s under Arrigo Saachi, though it is arguable that English clubs Wimbledon and Watford used a form of counter-pressing, turning the opposition with long balls into space and fighting for loose balls. The globalisation of football, with coaches moving freely from nation to nation, has seen pressing and counterpressing become commonplace.

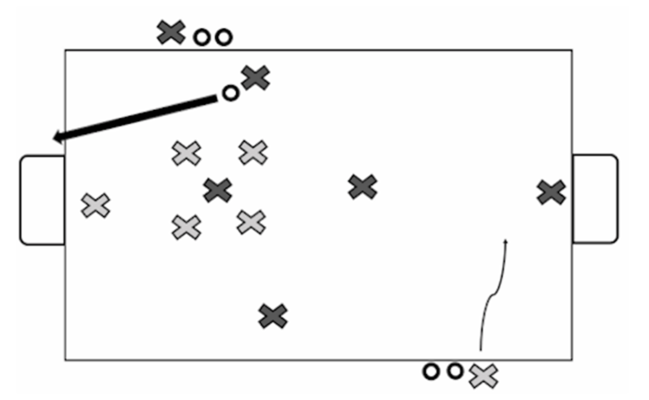

Counter-Attack

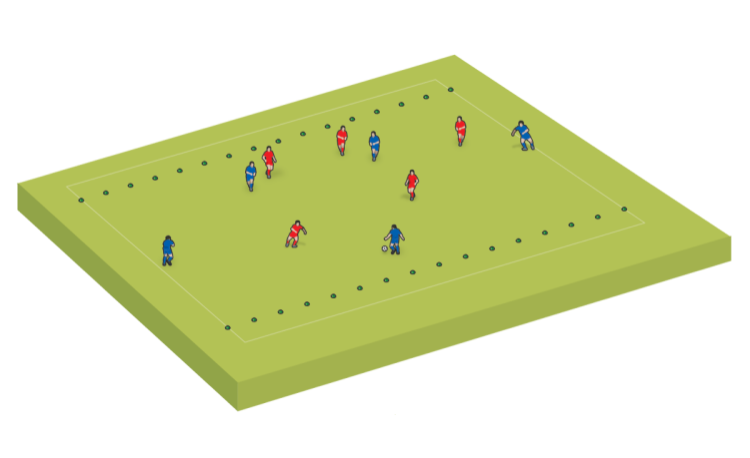

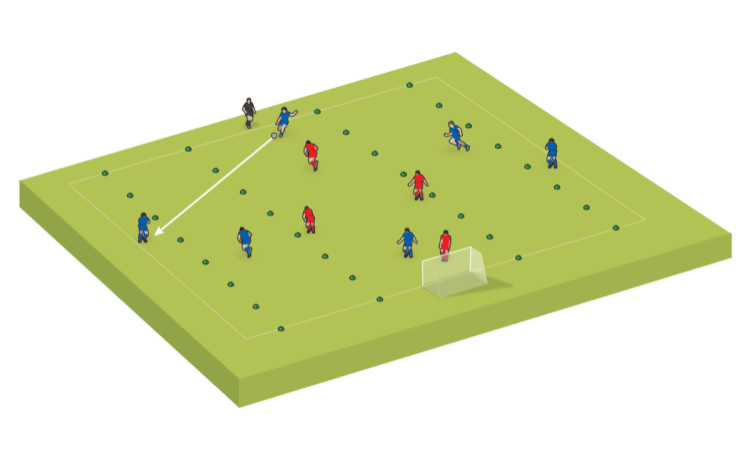

Both teams have a player positioned close to the opposition goal. Whenever the ball goes out of play, the player close to the goal restarts the game. They are free to dribble or pass the ball in to restart the game.

In the situation illustrated, the dark team have taken a shot and the ball has gone out. Rather than restarting with a goal kick, the grey player can attack the goal immediately. The players’ reaction to the transition needs to be quick to take advantage of the opportunity. The player who dribbles on can stay on the pitch until the ball goes out again. If it is their team’s possession again, they go to the position on the side to restart.

This practice will focus more heavily on the reaction of the wide player, teammates, and the defenders, rather than any initial forward pass that begins a counter-attack.

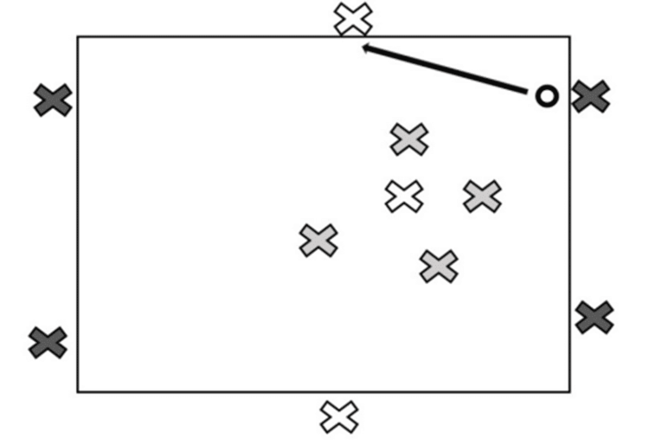

Counter-Press

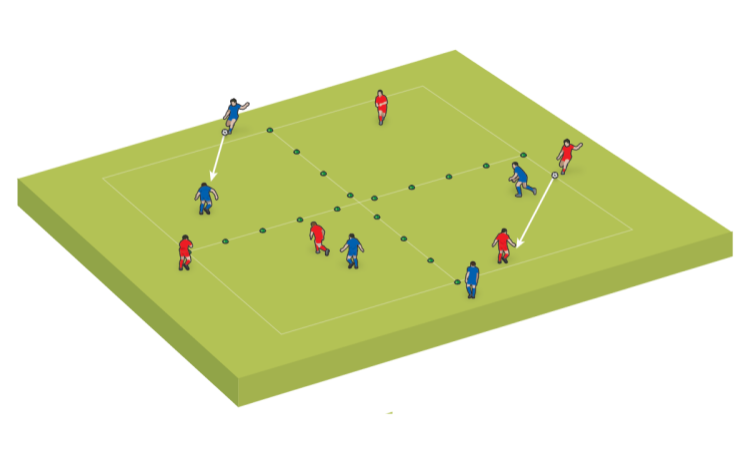

This exercise has been made famous by Pep Guardiola and is used by many coaches. The three white players support the team in possession, and the white players at the top and bottom are free to move anywhere along their line. The white in the centre may move anywhere inside the area.

The dark team are in-possession and have two players at each end. The four grey players create pressure to regain possession. Should they regain possession, the grey players take up the positions on the end, and the dark players now attempt to regain possession. The objective is for the game to be as fluid and fast as possible, but it will take large amounts of practice to get to that level.

At the transition moment, the team that loses the ball should not relax; they should pressure the ball with ferocity. Once the in-possession team have settled into position, the out-of-possession team will press with less aggression and – instead – look for triggers such as poor passes or the ball in the air. The out-ofpossession team may also be able to manipulate a situation where they cut off passing lines and isolate the player in-possession, one versus two.

UK and Europe

Click here to buy Football's Principles of Play

USA

Click here to buy Soccer's Principles of Play

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Discover the simple way to become a more effective, more successful soccer coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Soccer Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use soccer drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of soccer coaching since we launched in 2007, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.