Preparing your problem solvers

BEN BARTLETT looks at how teams can be drilled to recognise when the picture has changed and work out an effective response

When we select our team for any game, what resources do we and our players draw on to help us navigate the game challenges we will face?

Last month, we discussed the notion of value judgement in team selection, enabling the drivers shaping our club’s existence and the cares of the players and people involved to be central to the selection choices we make.

These influences are naturally coupled with the more traditionally understood team tactics we agree upon.

One of the aspirations in my own personal coaching development has been to support players and teams to be tactically adaptable.

While this in part pertains to playing different ‘systems’ - like 4-4-2, 4-2-3-1 or 3-5-2 - and encouraging players to practise solving the problems soccer presents within different organisational structures, there are broader connotations for adaptability than the arbitrary assigning of players to positions.

As described in my book Constraining Football, in a previous role I was part of a staff charged with developing an FA Women’s Premier League club (as the top flight was known at the time) into one of the top four in England with a holistic, fruitful development eco-system that supported longer-term sustainability.

"One of my aspirations has been to support players to be tactically adaptable..."

Part of this ability to compete successfully and in a sustained way, both within individual player careers and broader player and coach development programmes, was in enhancing our capacity to, in a resourceful fashion, adapt and change within different situations.

Our environment can consciously expose us to situations, appropriately, such that there is opportunity to learn the agility - across our entire connected human systems - to respond in the moment with varied solutions to the ever-changing, unpredictable nature of our sport.

This principle continues as a central element of my thinking. In my current environment, coaching staff possess individual responsibility for deciding upon the most appropriate tactics to support player development.

This individual responsibility is not whimsical or ego-laden; rather a genuine engendered ownership for our coaching staff.

This can support the players to develop in a way that both responds to what we understand about them and compete within the demands of the game.

These two things aren’t separate. If we dissociate the needs of the players from the demands of the game, we risk some misplaced, cult-like idealism in which we support players to develop in a way that doesn’t prepare them for their future.

Similarly, if we routinely impose the demands of the game onto people without understanding them and their current cares and characteristics, the lack of agency and interdependence this type of routine imposition can generate within people may negatively impact motivation. It can also negate the personal desire to understand how to own responsibility for growth and development.

This transcends coach and player development. Coaches developing the skill to support player growth in a more individually responsive way localises the detail that we coach.

This localisation of detail encourages the emergence of behaviour which is in-tune with individual needs and agreed upon as a consequence of what we grow to understand about each other.

This canonises each person, replacing standardised, arbitrary, top-down interventionist approaches - where coaches ‘do’ what academy managers decide and players ‘do’ what coaches tell them - with genuinely responsive coaching ‘detail’ that is owned and understood.

Consequently, what we see playing out in practice is unique not universal, compassionate not computational and aligned not arbitrary.

Finding solutions

Let’s illustrate this with an example - a youth team learning to play the game in a range of ways; adopting approaches and adapting solutions ‘in game’ rather than owned and driven by coaches or people perceived to be in ‘leadership’ positions.

This team of players and staff work at finding solutions they can utilise and adapt within different, ever-changing problems which they sense and feel in the moment.

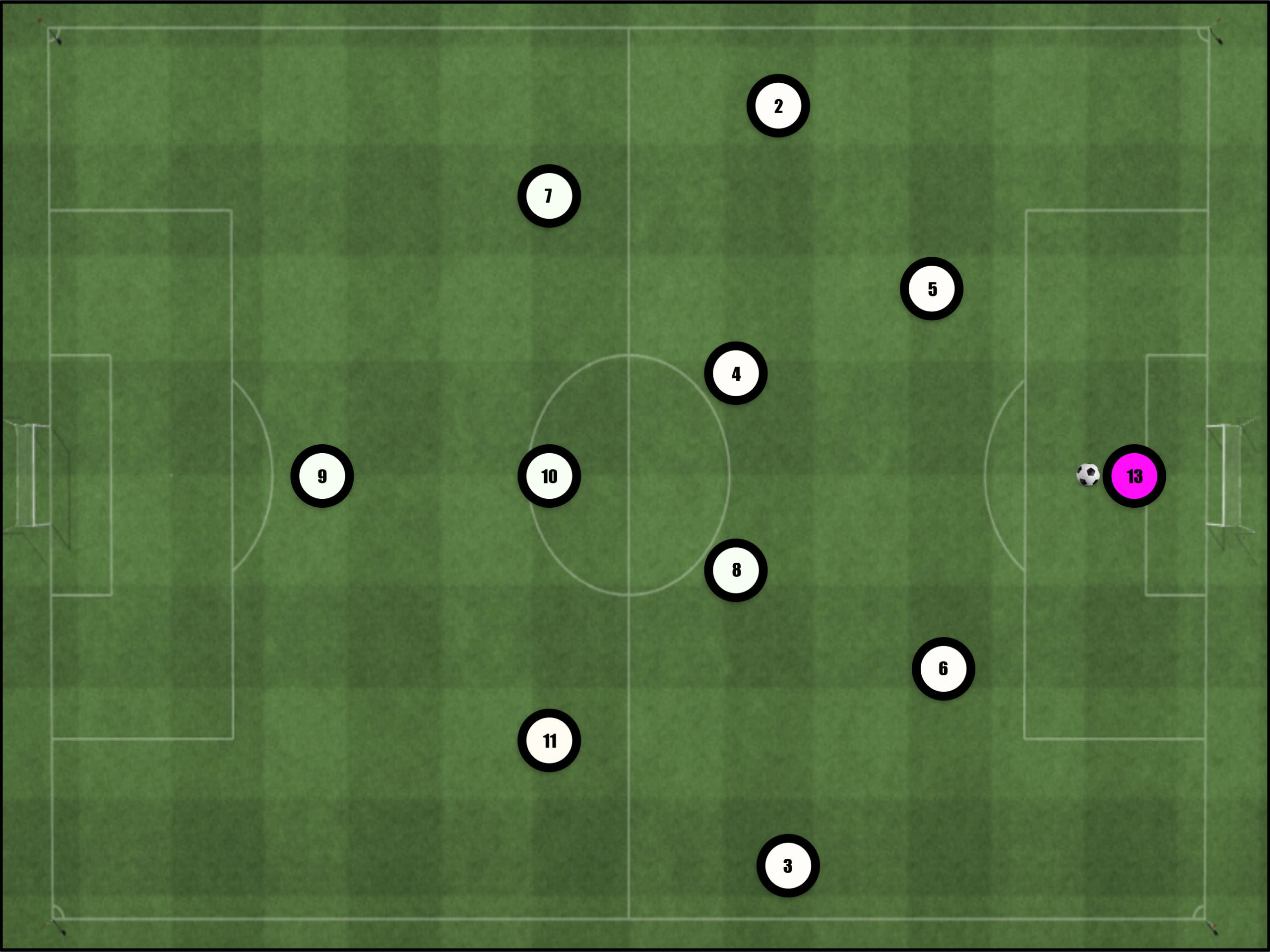

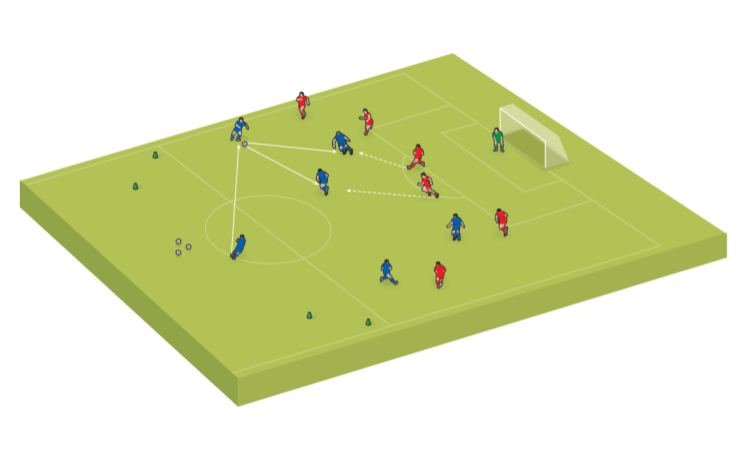

This particular group are, largely, organised into what might be described as a 4-2-3-1 (see diagram 1). In a recent game they faced a team who also set up, initially, in a 4-2-3-1.

Related Files

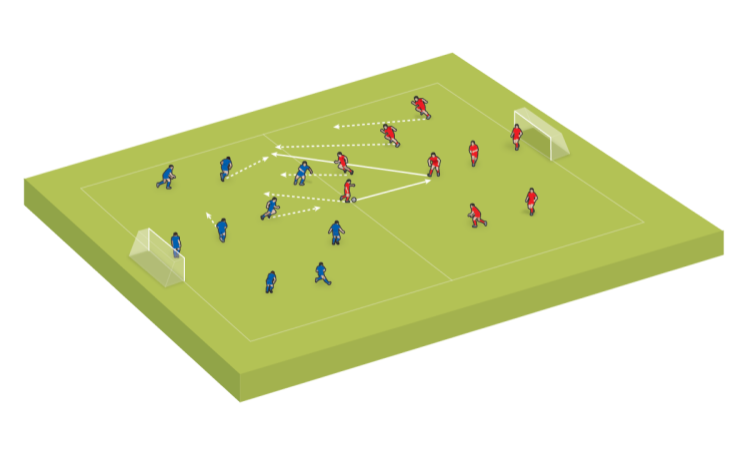

At half-time, though, the opposition shifted to a 3-5-2 as they were 3-0 behind, finding the game difficult and wanting to chase it. The problem to solve was how does the build-up play change, in game, when the situation changes.

This group, while spending time preparing deliberately for each game, ensures this preparation doesn’t offer single solutions to the perception of the game problem.

So, rather than only identifying that the opposition is playing a 4-2-3-1, the group look at possible solutions when the opposition press with one forward, with two forwards, when they only have wing backs in wide areas, when a midfielder from the opposition releases etc.

These solutions are subtly and cleverly layered into every practice session, and all other aspects of the coaching programme, including video work, to ensure there are no generic, non-responsive, global solutions to the problems the players face.

These solutions aren’t taken out of their hands by them being told to ‘do this’ when the opposition ‘do that’.

Players instead are supported to understand some of the broad problems that may be encountered and some potential solutions that might support them.

These solutions are implicitly and more explicitly evident in every aspect of how and what is coached.

Hence, players are learning and becoming better resourced to respond and adapt solutions when the problem changes, like in the recent game when the opposition changed their system and the intensity of their pressing.

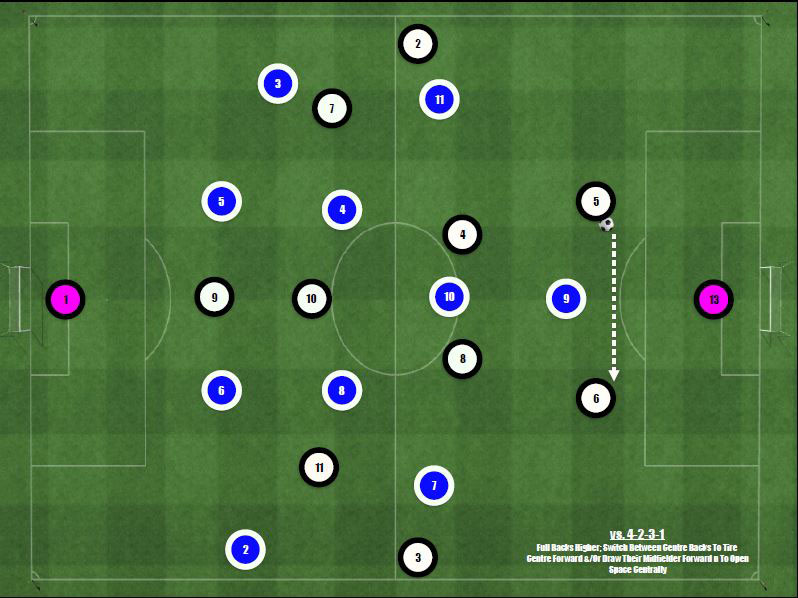

Fig 2, above, highlights some of the possible solutions when the opposition play a 4-2-3-1 and are initially less intense with their pressing.

In this illustration, the opposition only have one forward, meaning one of the centre backs is free.

Tentative solutions in this situation are for the centre backs (and possibly the goalkeeper) to move the ball across the pitch to ‘run the legs off’ the centre forward.

If the opposition then release one of their midfielders to help press - so they are now pressing with two players - the full-backs being high may have created space centrally to play through them.

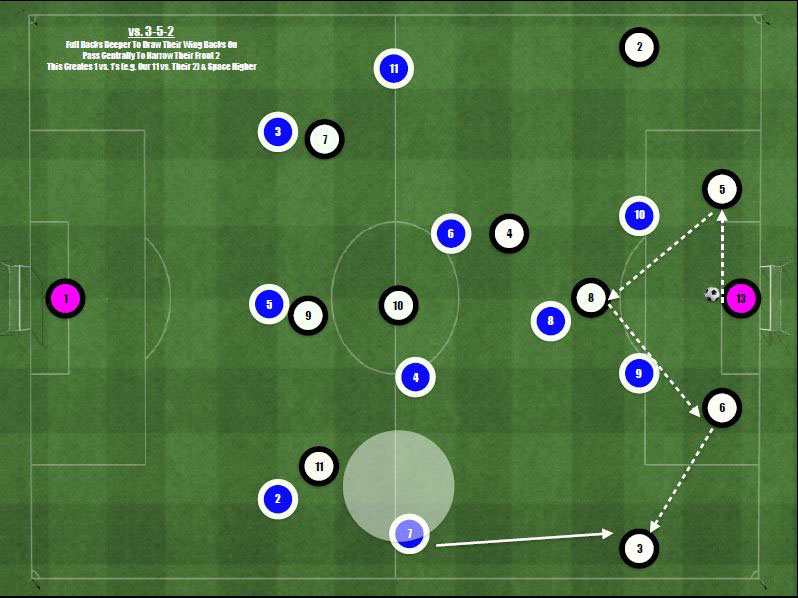

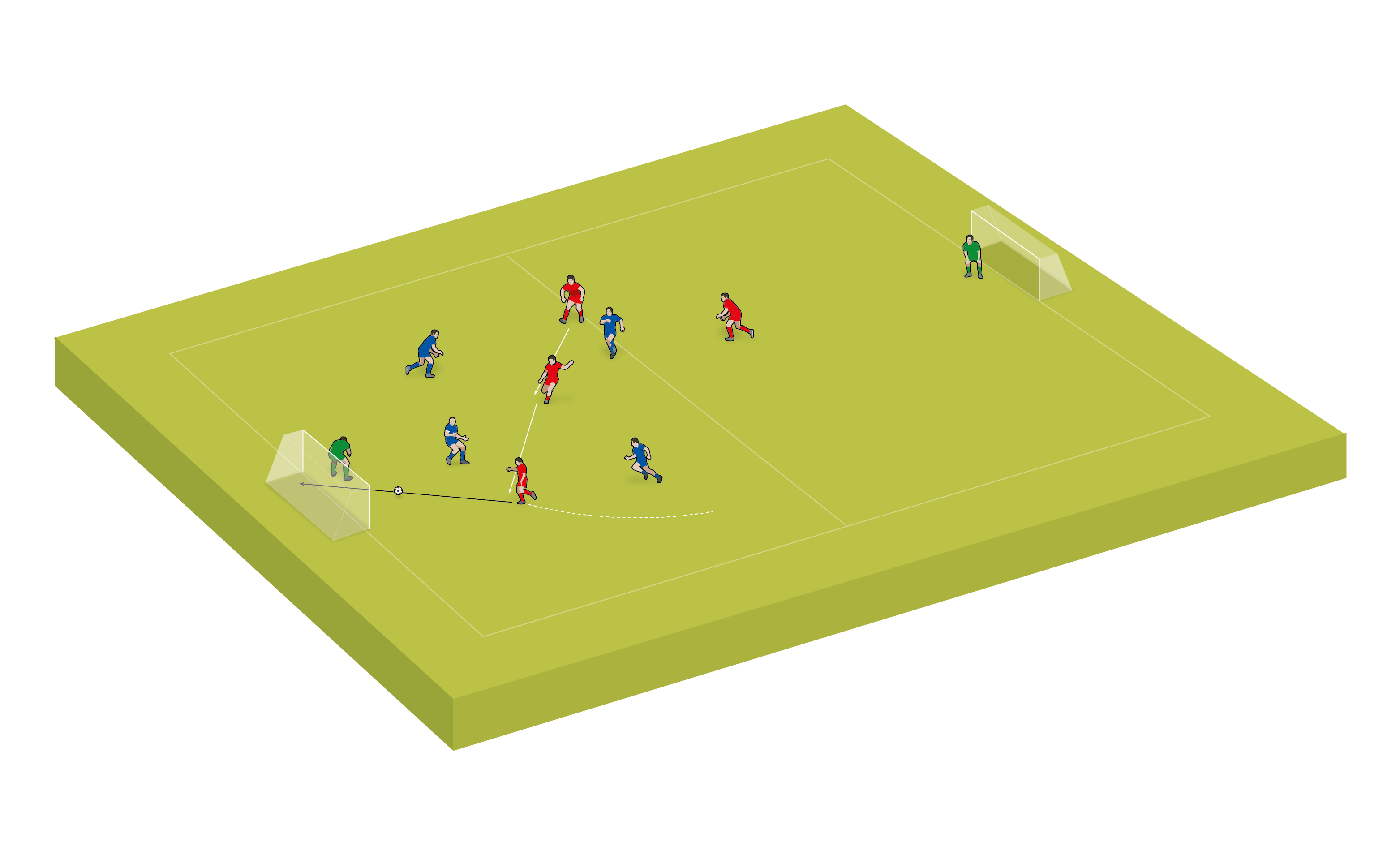

At half-time, the opposition changed to play with a 3-5-2. The coaches didn’t know this until after the second half started so hadn’t planned for it at half-time.

However, the coaches have had the foresight to expose players to different problems that they have practised and been supported to solve. This meant the players recognised the change in the opposition and reverted to different solutions ‘in game’ (see Fig 3).

When the opposition shifted to a 3-5-2, pressing higher and with more intensity, the possible solutions are different.

They include players, particularly the full-backs, moving deeper to stretch the oppositions press, teasing the opposition wing-backs up the pitch and creating space for 1-v-1s nearer to the oppositions goal.

These solutions connect across players. If the centre-backs have been encouraged to demonstrate the courage and belief to pass short and centrally near to their goal it can narrow the opposition, creating space for the full-backs to receive.

To repeat, these solutions connect into practice sessions. If we haven’t designed, in league with the players, practice sessions that provide both representative, game-relevant situations to practice in, and supported the players with possible solutions, then it is unlikely we can expect them to directly perceive these situations as they emerge, and change and respond positively.

“The desire for tactically adaptable players is aligned to our behaviour…”

If we are armed with single solutions to problems, what does our human system do when that single, patterned, convergent answer fails us?

The desire for tactically adaptable players and teams has to be aligned to our behaviour.

If we expose players to challenging, problem-focussed situations, navigate them collectively and, importantly, hold our nerve as we are going through the messy, sometimes chaotic and unsettling nature of ‘learning to learn’ in this way, then the players can win in multiple ways – as this team did.

They won the first half 3-0 and the second half, against different tactics, 2-1, defeating their opposition 5-1.

They also won in terms of recognising that the commitments they have collectively made to grow and develop together – which have been steadfastly upheld even at times of perceived pressure – are valued and critical towards positive change.

This positive change supports the group to, both individually and together, continue to deal with the challenges of life and of football.

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Discover the simple way to become a more effective, more successful soccer coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Soccer Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use soccer drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of soccer coaching since we launched in 2007, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.