Maintain principles in larger-sided games

In his latest article, BEN BARTLETT explains how to encourage adaptable skills in bigger-sided practice matches, through formations and design of sessions

The conceptual principles explored in last month’s column (SCW Jun 3) provided a backdrop to how we can encourage the development of adaptable skill through environment design, particularly in training.

Those principles were embodied within smaller-numbered practices. However, they don’t need to get lost in bigger games.

We can continue to be thoughtful about how we position certain players, both relative to their team-mates and direct opponents.

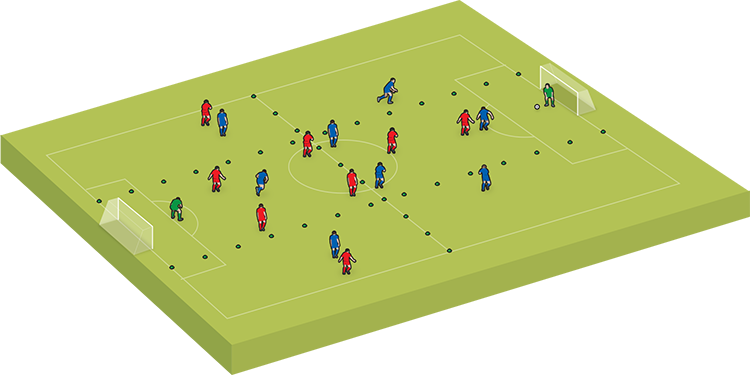

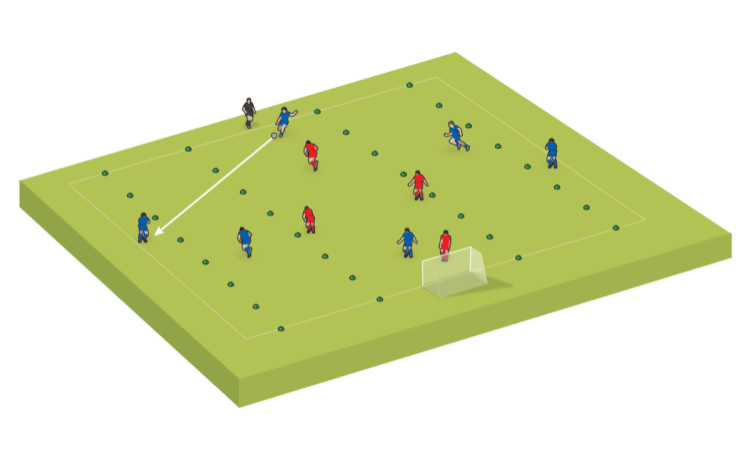

Let’s first look at a 9v9 game (fig 1, below) on a large pitch, split into three thirds. Two different formations are used - the Reds in a 4-3-1, to retain the defensive and midfield units of a 4-3-3, along with a lone forward, and the Blues in a 3-2-3, to reflect the defensive and forward units within a 3-Box-3, plus two from that midfield box of four.

Organising the players in these ways in practice helps them experience games more representative of competitive fixtures.

Not having 22 players doesn’t mean we lose the frames of reference from the 11v11 game. In fact, it is an opportunity to heighten certain opportunities by thoughtfully constraining the game in these ways.

The Reds in this game have a focus on their defending, particularly being aggressive higher up the pitch to affect a regain in the opposition’s half.

If they succeed, and consequently score, it is rewarded with three goals – because what gets rewarded gets repeated.

The Reds must have the courage to leave their starting positions in the defensive or midfield lines, the physical capacity and desire to run towards the opposition and the social cohesion to perceive what others are doing, trust in them and back them up.

The Blues are likely to drop defensive players deeper to try and stretch the pitch and draw the Reds higher up the pitch, creating vertical space between the units that can be exploited with passes or dribbles.

Concurrently, the Blues have a focus on switching play. Complementing one team’s focus with something directly oppositional enhances the intensity of the game.

As the Reds attempt to steer and direct the opposition to initiate regains high up the pitch, the Blues seek to free themselves from this opposing task constraint to work the ball, in a variety of ways, to the opposite side of the pitch.

This is likely to enable a powerful environment of competition, where, if the challenge is pitched appropriately, players can practise at, or beyond, game intensity.

To repeat, this can constellate our methodology away from coaching one team or one theme to supporting players to learn the game in an integrated, holistic fashion.

For the Reds, in solving their pressing problem, there is no one specific player who should release themselves higher to seek to win the ball back, nor are there universal triggers - like a backward pass - that always lead to a certain response; context will guide the decisions.

Specific prescriptions are unlikely to take account of the dynamic nature of soccer nor empower the players to understand how to respond dynamically. Contextual factors such as the score, remaining time and particular player matchups or attributes are some of the factors that may influence decisions.

However, there are some more common possibilities within the laws and guiding organisational constraints of soccer.

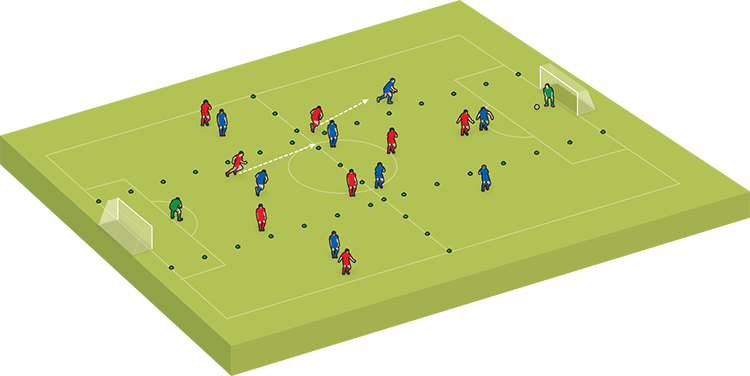

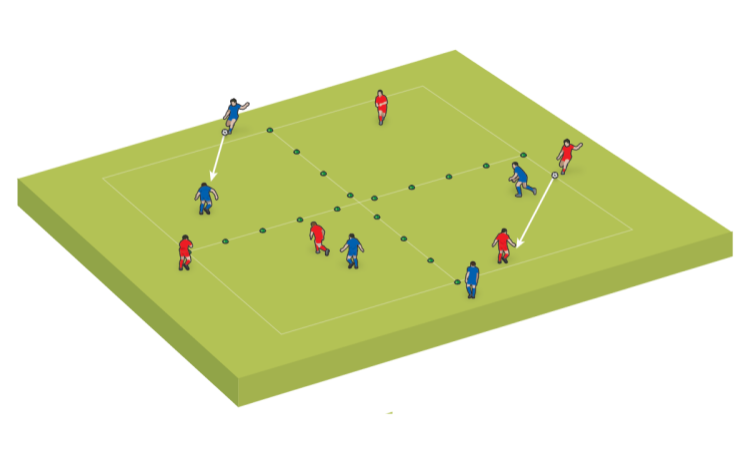

For example, as illustrated in fig 2 (below), if one of the outside centre-backs within the Blues’ back three positions themselves just outside the vertical thirds, it may be that one of the Reds’ deeper midfielders will release as the ball is played. This can be supported by the centre-back on that side of the pitch stepping onto the Blues’ midfielder left free.

While it is fair to say the Reds’ advanced midfielder may be the better player to fulfil this screening role, this perhaps makes it hard to continue an aggressive press in the event the ball is consequently played back to the Blues’ goalkeeper.

The centre-back releasing also keeps the direction of the Reds’ press going towards goal. It may also lead to the opposition playing a longer ball which can often be a consequence of aggressive pressing.

However, organisationally, starting a game with numerical superiority in deep areas - rather than with more positioned higher at the outset - perhaps negates that decision in the formative part of the Blue team’s build.

This is perhaps another benefit of the Reds having full units in defence and midfield.

Naturally, through both the inherent flow of soccer and each team adapting their behaviour in response to previous situations, the Blues are likely to move into different positions to find ways to play out from their goalkeeper. This is likely to influence who releases to press and how they do it.

Related Files

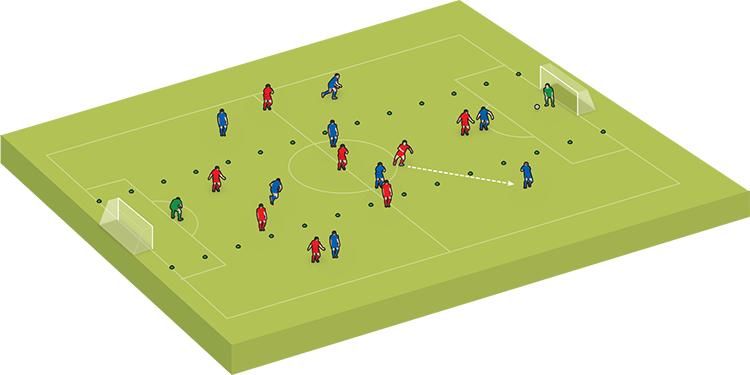

For example, in fig 3 (above), the outside centre back for the Blues moves higher and wider to make it harder for the Reds’ midfielder to press. It is possible the full-back on this side of the pitch releases to press onto the outside centre back.

It is unusual for a full back, in the 11v.11 game, to be in a situation where they would press onto a centre back. However, it is more of a recognition of what might trigger the press rather than a specific pressing ‘rule’.

"Different approaches to pressing will give diverse defending experiences..."

An opposition player who is moving higher and wider is likely to prompt a deeper, wider opponent to engage with them.

The response of the nearest central defender is, again, highlighted. In place of them releasing forward into midfield, as in the first example, they release to the side to look after the Blues’ wide forward.

The sideline is a support for this press as the Reds can use the natural demarcation of the side of the pitch to limit space and force the Blues into areas that enable the Reds to assume greater control of the pitch and be better situated to generate a turnover.

The variety generated from different approaches to pressing affords players exposure to diverse defending experiences.

Centre-backs developing the human skills to press, by controlling their speed in running forward quickly into midfield, sideways and in preparation to run backwards to defend the channel, and the associated 1v1, cat-and-mouse defending skills that these situations provoke, is important.

Those skills being embedded into games ensures players are challenged to adapt their behaviour in response to the circumstance.

This is preferable to players being taught rote solutions that some player development programmes can be littered with, in the hope players can then import what is often lacking in many contextual elements into games.

What are often referred to as ‘extreme 1v1s’ are an example of this – where players practise 1v1 without any other players, direction or scoring solutions.

In these ‘extreme 1v1s’, much of the perceptual information that shapes our decisions in the game are removed to, arbitrarily, practise 1v1. In soccer, it’s never only 1v1 - there are other things influencing what we do with and without the ball.

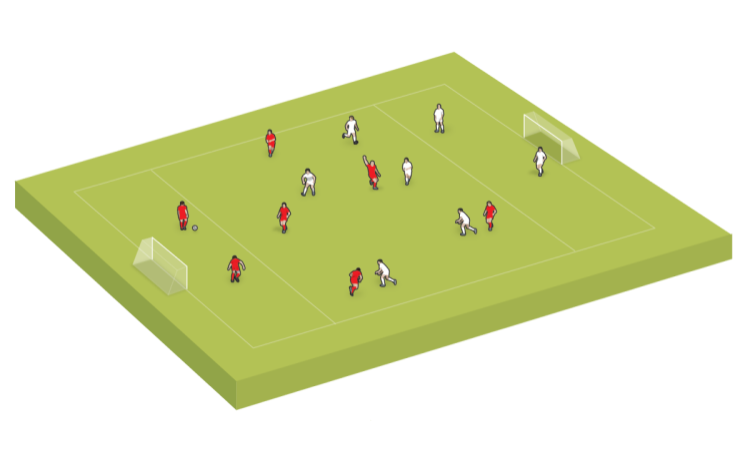

The final illustration details this point. The outside Blues centre back this time moves deep and stays narrow. This is the moment to tease the Reds’ advanced midfielder out to initiate the press (see fig 4, below).

There are some important individual defending skills players can practice and have their attention drawn towards - yet these skills are continually being influenced by each player’s proximity to the ball and the other players on their team.

The Reds’ players, for example, mark ’ball-side’ - horizontally, the side of the player that the ball is - and close enough to either step in front to intercept or prevent their direct opponent receiving and turning.

The players who are further away, such as in the Reds’ defensive line, also need to be cognisant of the space behind them, taking up a position that takes into account their capabilities and those of their opponents.

For example, if I am very fast at running I might go tighter to my opponent as I am confident in my ability to win the race should the ball be played into space behind me. Conversely, if my direct opponent is very quick, that might lead to me adjusting my position somewhat.

Further, the Reds’ midfielders are challenged to defend their direct opponent but also need to be aware of the space behind them. They must be able to screen passes into the Blues’ forwards, and/or attempt to steal the ball from the front in the event it makes it there, as well as tracking opposition midfield runners.

The left-sided centre-back for the Reds, the one furthest from the ball, is also fulfilling multiple defending roles.

Principally, this defender, within a back four, is typically the one to take up the deepest position, nearest to our goal, to provide cover behind their centre-back partner as well as having their body positioned such that they can defend a diagonal pass to their direct opponent over their shoulder.

In connecting to the players’ individual needs or strengths, this is something we might organise deliberately.

A player on the Blue team - working on longer diagonal passes and playing as the outside, left-sided centre back - being challenged to try to find their right forward on the opposite side of the pitch, might be one way we could switch play.

This player can be encouraged or conditioned to practise this more frequently than other ways of using the ball, providing both a direct benefit for them and a connected experience for the left sided Reds’ centre back who gets enhanced opportunity to practise defending these types of passes.

"In soccer, it’s never only 1v1. Other things influence what we do on and off the ball..."

Within the planning process, there is potentially value in organising teams such that players who may benefit from a heightened focus on pressing and working together to effect regains are able to spend more time in the Red team, while those with greater focus on individually and collectively playing within and past heavy opposition pressure spending an imbalanced period of time on the Blue team.

Additionally, we might add additional demands to increase the frequency with which the Blues play out from the back or allow the natural ebb and flow of the game to support players to practice with a greater degree of game variation.

All the elements highlighted in this game, and many other thoughtfully designed games, are connecting and occurring simultaneously.

This can appear complex, so it is beneficial to stay within a single practice for longer periods, over consecutive sessions, weeks, months and into gamedays, repeating similar practices and principles in subtly different ways - varying different pitch sizes, with some slight shifts in the parameters implemented or the demands we agree the players can be challenged by.

Players and coaches can benefit from time enjoyed experiencing the complexity of the game, deepening understanding and awareness of the territory that is the game of soccer.

If the player development programme continually jumps from specific theme to specific theme; if we feel compelled to break the game down into minute, constituent parts and coach the detail in a step-by-step, flat-pack constructionism, then we run the risk of not supporting the players to learn the game of soccer.

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Discover the simple way to become a more effective, more successful soccer coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Soccer Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use soccer drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of soccer coaching since we launched in 2007, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.