Keeping it realistic

In the first article of a three-part series turning research on learning environments into practical advice for coaches, JAMES MAYLEY urges a sharper focus on game-like drills

Creating the right learning environment is a big challenge for coaches.

However, get it right and you can optimize psychological, tactical, technical and social growth.

Research into learning environments often revolves around the ‘TARGET’ model - Task, Authority, Rewards and Relationships, Grouping, Evaluation and Time.

Managing these factors can help coaches in creating an environment which promotes long-term learning and development.

This article will look at the role of task design within the learning environment.

What does task design look like?

Effective task design requires consideration of where players are in their development and what they need to continue to improve.

Tasks should ensure that training occurs in a game-realistic context, allowing players to learn how, when, why and where to perform certain actions at a challenge point appropriate to their needs.

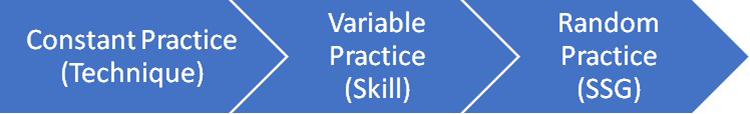

Tasks can be structured so that skills are practised in either a blocked or random manner, under constant or variable conditions.

Traditional session designs typically spend significant time in blocked, constant tasks. Here, the same skill is practiced repeatedly in the belief that uninterrupted time on task will cement the movement skill into muscle memory and allow the skill to be transferred into games, which are played at the end of the session.

However, there is increasing evidence that traditional session designs, as they are normally used, may not be the most effective way to develop footballers.

Traditional Session Designs - Limitations and Possible Adaptations

1. Transferability of constant technical practices

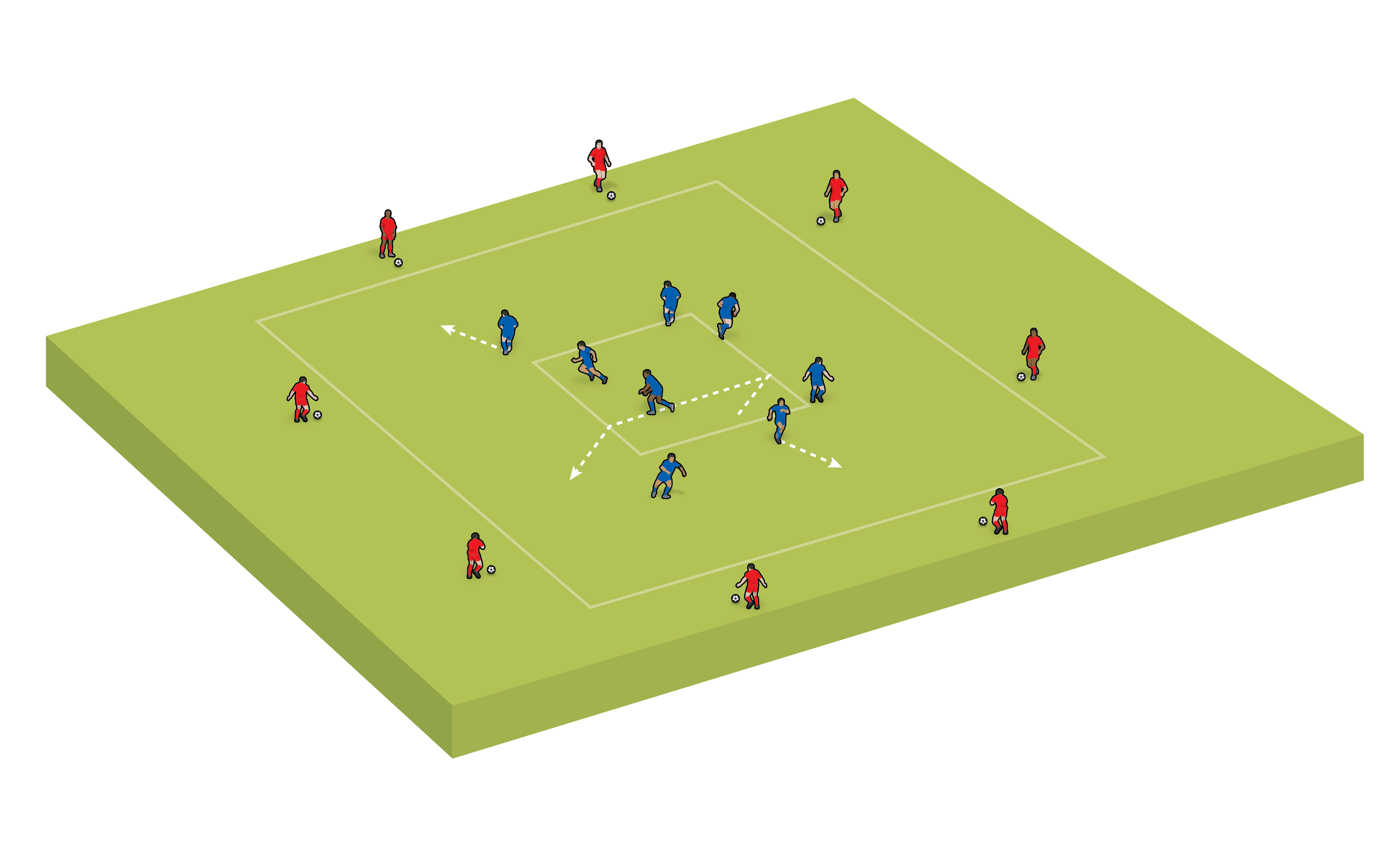

Constant practices mean a skill is only practised, and therefore learnt, one way.

For example, it is common to see young players passing the ball back and forth to each other in straight lines to develop their passing and receiving skills.

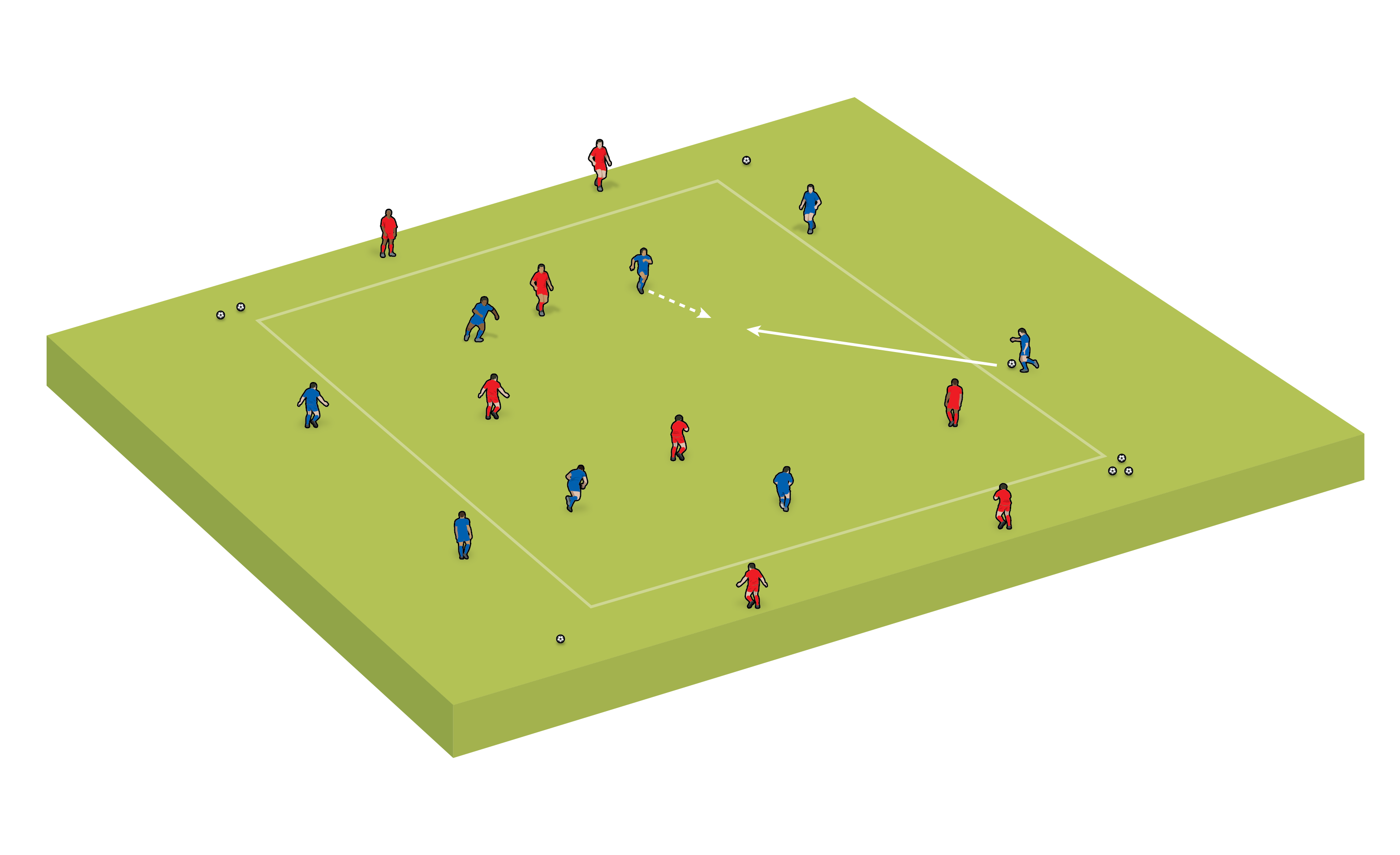

However, games demand that players pass and receive balls from various angles, weights and distances under varying levels of pressure from opposition players.

Now, imagine children are moving around an area, passing and receiving on different angles and distances while having to find space and negotiate other players. Suddenly, that technique is being developed in a context closer to the demands of the game.

Another example is the typical, straight-line, 1v1 dribbling skill practice used by coaches throughout the game.

Have you ever seen this exercise performed with the attacker receiving a pass from various angles, being closed down by a defender from different start positions and being challenged to beat that defender in different directions?

These simple adaptations increase the variability of the task, allowing dribbling skills to be developed in a more transferable and realistic way, but it may not be something you see or use often in coaching sessions.

2. Player memory

Players start forgetting what they have learned as soon as training finishes.

Trying to ensure learning takes place in an environment which can help overcome this forgetting process is critical. Technical practices typically lead to high performance gains in practice but poor long-term learning.

This can create an illusion that players are improving, only to find they are unable to perform at the same level on gameday.

Alternatively, when challenged to engage in tasks at a higher level of difficulty and with more randomness in skill execution, players demonstrate greater retention of the skill and understanding in the future.

Related Files

3. Time on relevant tasks

Traditional sessions usually finish with a game-based activity related to the skill or technique being practiced.

However, studies have consistently shown that coaches often spend too long on early practices, therefore limiting game time.

Borussia Monchengladbach goalkeeping coach Fabian Otte, who also holds a PhD in skill acquisition, interviewed 15 goalkeeper coaches working at an elite level for a study.

He found that, while they valued decision-making as the most important skill for a goalkeeper, their session design meant it was the skill rarely practised during training, due to the time spent on constant, technical practices at the start of sessions.

Ensuring sufficient time is dedicated to later tasks is therefore vital for coaches using a traditional session design.

AN ALTERNATIVE: GAME-BASED APPROACHES (GBAs)

GBAs encourage player development through playing games, and they help answer the increasingly common question: ‘Does training look like the game?’.

When used effectively, GBAs allow players to learn not just how to perform a skill, but also when, where and why within a game-realistic context. They therefore allow skills and game understanding to be developed simultaneously.

There are a number of common misconceptions regarding GBAs.

The first is that players will develop simply by playing the game. GBAs require coaches to guide learning through a combination of instruction, questioning and carefully planned constraints.

A core principle underpinning GBAs is that players are given time to reflect on their learning and solve problems, typically through coach-led questioning or small group discussions.

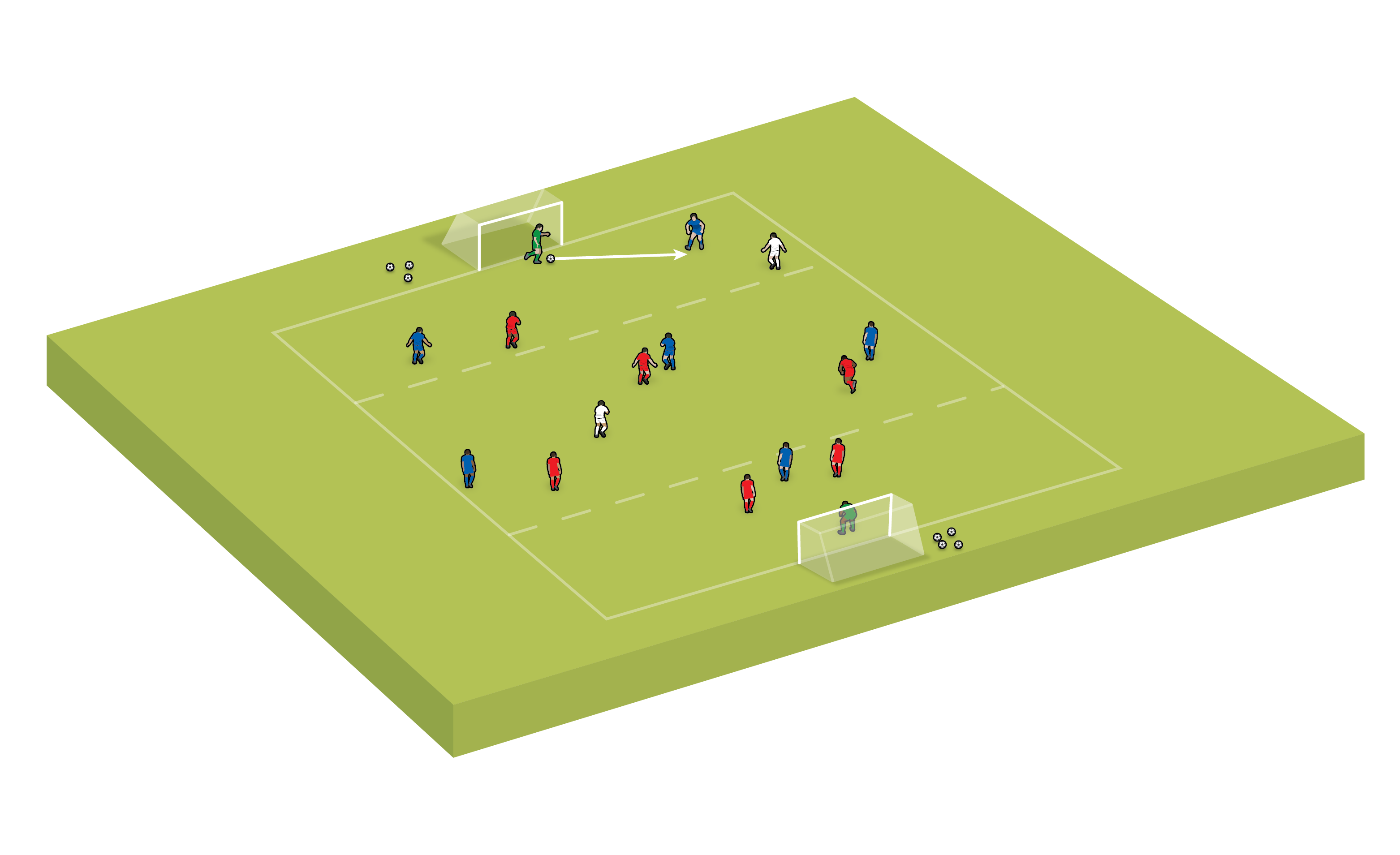

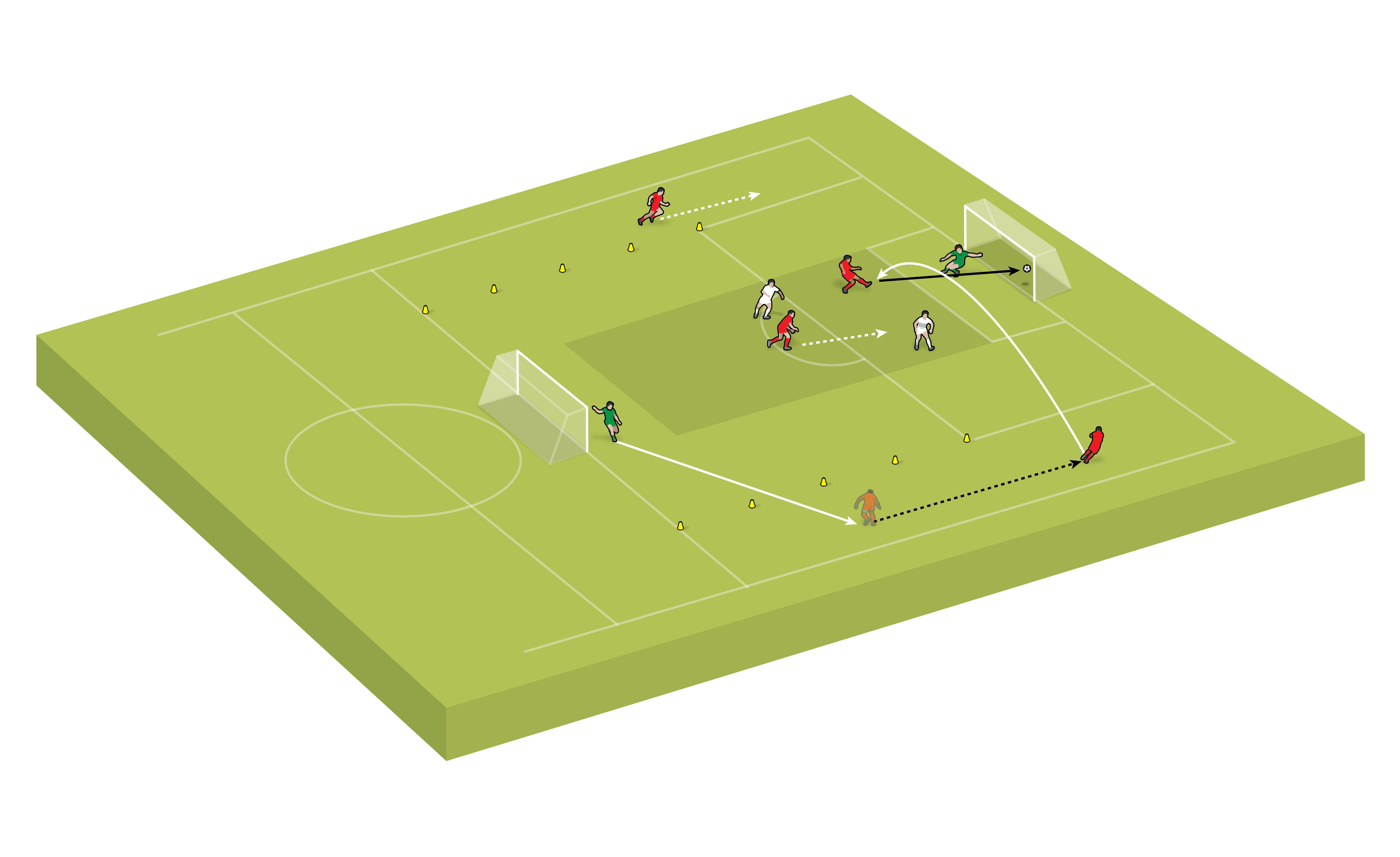

Constraints also play a key role in GBAs. These can include varying the number of players, the field dimensions, the number and/or location of goalscoring targets, equipment and rules.

Rule constraints can be further broken down to allow coaches to restrict, relate or reward specific behaviours.

Restrict: A constraint like ‘make five passes before scoring’ creates lots of repetition, at the significant expense of game realism and allowing of positive decision-making.

Relate: Something like ‘look for chances to build from the back before scoring’ will maximise realism and decision-making, but may not sufficiently motivate learners to practice the desired action.

Reward: ‘The number of passes you make is the number of points you get if you score’, balances repetition and realism.

"Rule constraints allow coaches to restrict, relate or reward specific behaviour..."

A second misconception of GBAs is that players only play games. Not so. Coaches should take a more pragmatic approach in their implementation of GBAs.

In an example of how to combine traditional coaching methods with GBAs, the USSF have adopted a Play-Practice-Play (PPP) approach to session design.

This first involves a game-based activity, often a simplified version of the full game. This initial game allows players to practice and build an understanding of the topic in a context-relevant setting.

Following this initial game, coaches are encouraged to allow players to reflect via a Q&A before delivering a practice activity outside of the game setting. This activity is designed to allow greater repetition and a narrower focus on the topic area.

Coaches may also maintain links to the game with a realistic pitch location or asking open questions (’when/why might we do x?). The session ends with another, typically more challenging, game-based activity.

To assist coaches in their session design, the USSF provides four guiding questions: 1. Is the practice organised?; 2. Is it game-like?; 3. Is the it sufficiently challenging?; and 4. Does it allow for repetition?

KEY TAKEAWAYS

The question we should ask is not which types of task are best, but when and why we should use different approaches.

Athlete-centred coaching requires coaches to be in tune with each player’s needs and adapt their approach accordingly.

This is not to say coaches should never use constant, technical practices. The skill of coaching is knowing when, and more importantly why, to use a specific approach.

However, it may be time to question if they should form the bedrock of every session we coach.

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Discover the simple way to become a more effective, more successful soccer coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Soccer Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use soccer drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of soccer coaching since we launched in 2007, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.