How youngsters learn - and how you can help them

John Allpress, ex-assistant head of academy player and coach development at Tottenham, on the theory of learning and practice and applying it to coaching.

We are not defined by our experiences, rather what we learn from them.

The brain cannot see the future. It works from experience and memory in a world where nothing ever happens in exactly the same way more than once, but many very similar things happen a lot.

Driving to and from work is a good example of this. The route and what occurs every day are very similar but will never be exactly the same.

There could be more traffic one day, different weather conditions or works taking place that cause a diversion. Drivers are required to use their experience to negotiate the way safely.

The more they drive the route, the more experienced they become, and the better their decisions along the way are likely to be.

The four stages of learning

Unconsciously incompetent

An individual does not know they cannot do something, as they have no knowledge of its existence. For example, a Roman soldier doesn’t know they cannot drive a car as they have never seen one.

Consciously incompetent

An individual knows something exists and knows they cannot do it. For example, someone knows a car exists but they have never taken any lessons and know they cannot drive it.

Consciously competent

An individual can do something but has to think about it while doing so. For example, someone can drive a car but has to think about what they are doing as the car is moving.

Unconsciously competent

An individual can do something without having to think about how to do it. For example, someone can drive a car without thinking. The skills have become automated and the driver can fully concentrate on decisions that have to be made.

Once they can kick a ball and run around, most players spend their time moving between the consciously competent and unconsciously competent stages of learning as they learn new things and practise more.

After reflecting and reviewing, players will:

- Commit the new knowledge and new ways of doing things to memory

- Make modifications to their behaviour or how they go about things

- Make the links with what they already know and can do more permanent

Now, players’ decisions can be more informed, they can do more and be more effective, efficient and reliable.

They will have better prediction skills as to what is likely to happen as they see situations begin to unfold. They become more experienced at dealing with what could develop.

What to do with what you learn

Once people know what to do, they are in the consciously competent or unconsciously competent stages and other motivations can take over.

Are they happy to simply be able to do something, or do they want to be the best they can be?

Once someone can ride a bike, for example, they may simply be happy that they have got an efficient way of getting from A to B. Or, they may have aspirations of being a professional cyclist or an Olympic champion.

If it is the former, they can be safe in the knowledge that they will never forget how to ride a bike. They can jump on it once a week and ride to the shops with confidence.

If it is the latter, however, they must practice a lot, in a focused, deliberate way, so that they can make the required modifications to their skillset and tactical knowhow and keep improving.

What is practice?

Practice is what you do when you do know what to do and want to get better.

If you don’t know what to do, you can’t practice. Think of chess, drawing, maths, brick-laying, riding a horse, driving a car, riding a bike, any sport or game. In fact, anything at all. Everything requires you to learn before you can practice.

Practice will improve things fast, as long as it is focused and deliberate. This is where the teacher or coach and their knowledge comes into the equation.

Practice makes permanent. The best teachers and coaches – and they are effectively the same thing – take time to get to know their pupils or players and what they need to do to get better.

What is good coaching?

Good coaches have the following attributes:

- A deep knowledge of their subject

- An understanding of how learning and practice work together and complement each other

- The knowledge that learning and practice works simultaneously on three levels - people are learning how to do things; practising how to use things; and developing the habits of mind necessary to keep going

- An understanding of how to incorporate learning and practice into their work with players

- They promote good habits by role modelling behaviours that encourage progress over perfection

- The knowledge that a positive environment is crucial if effective learning and practice is to take place. This involves patience, tolerance, understanding and having the players’ backs 100% as they navigate their journey of exploration and discovery

- Personalising the learning and practice as much as possible. Youngsters like it when they think its about them, so if the coach can challenge individuals effectively in training and matchplay, this will help information become more deliberate and focused on a player’s needs

- Have a variety of intervention strategies at their disposal, including asking the right questions in an open-ended fashion, giving instruction, offering demonstration, presenting challenges, conditions and constraints – all of which cultivate learning and make practice focused and deliberate

Related Files

Good coaching in action – the whole, part, whole method

The younger or less experienced players are, the more links and associations they need to establish to build experience and make progress.

To this end, a teaching method known as whole-part-whole, or play-practice-play, can be helpful.

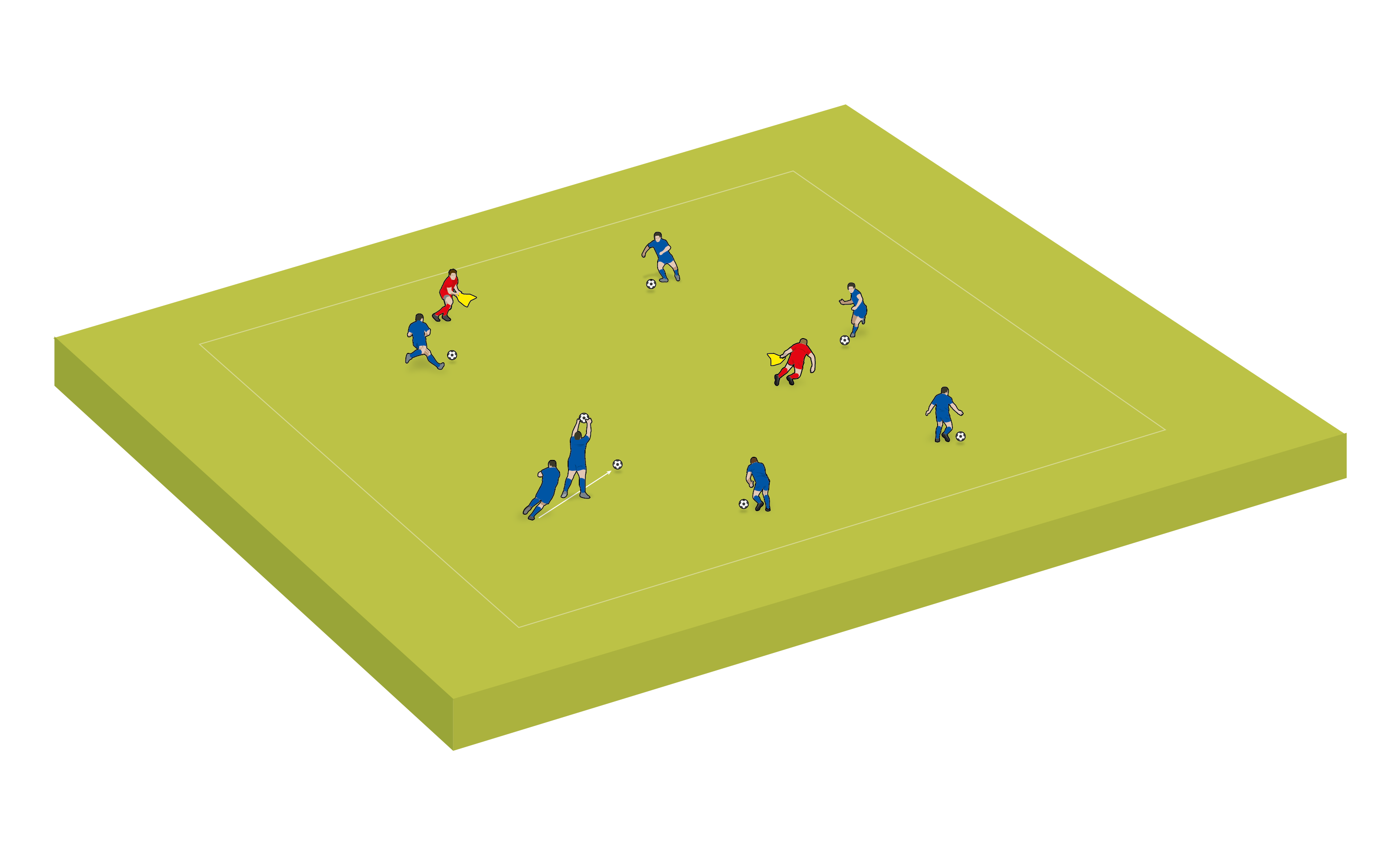

Part 1 - whole

This method involves starting training by playing a focused game, where the players begin to make sense of where something fits in the game.

Let’s say the focus of the session is receiving and turning. Within the game, the challenge for the group could involve players letting the ball run across their body and playing forward as a first action.

In this way, the players will start to understand where receiving and turning fits in the game and they will begin to make links as to where it should and should not be attempted, where it works and where it doesn’t.

The challenge will also help to focus the coach on the players’ endeavours, struggles and successes and open the doorway for help if it necessary.

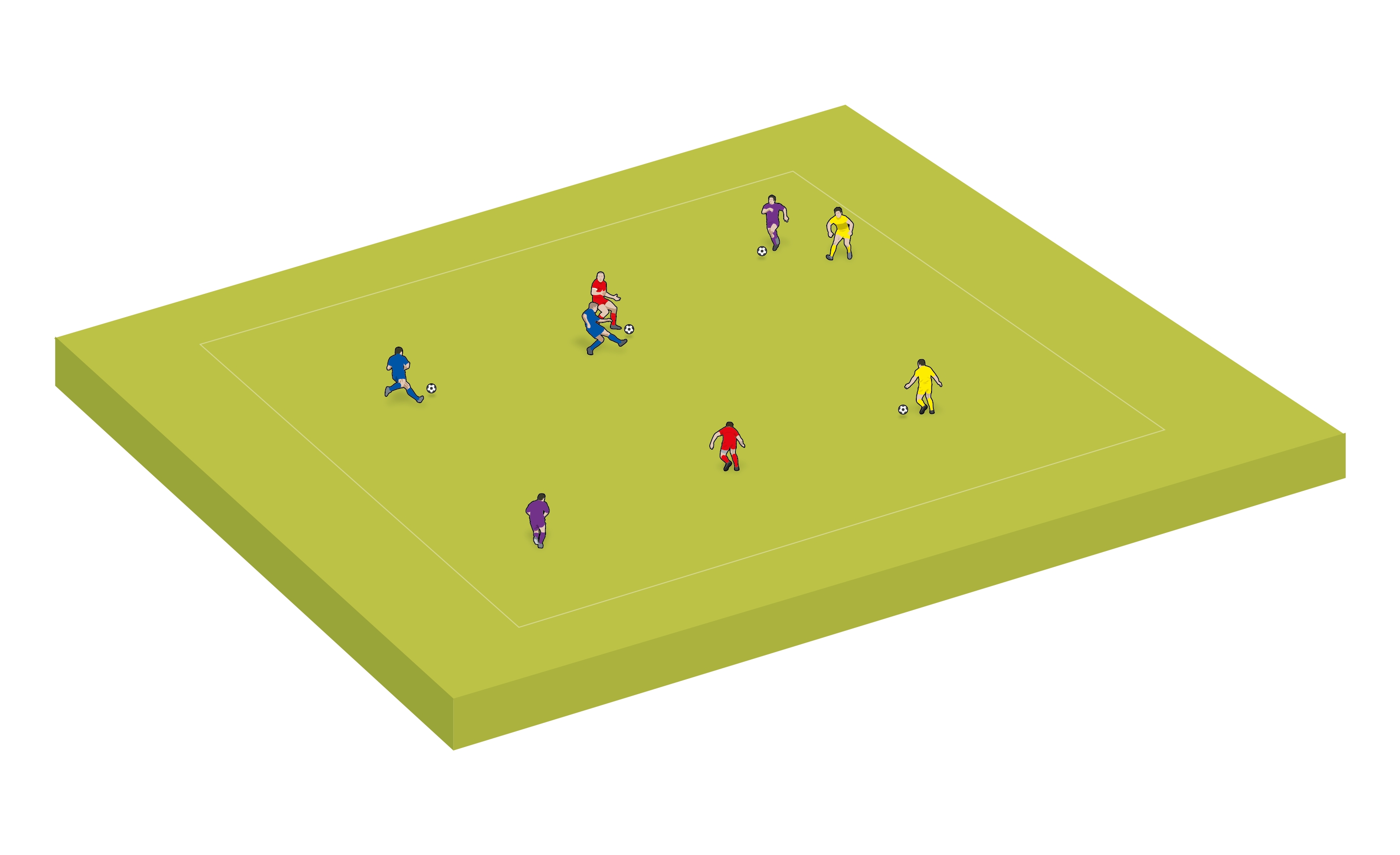

Part 2 - part

The coach can then break the work down into a part practice that is more deliberate, focused on turning with no touch, one touch or multiple touches, for example.

In the part practice, the players get more opportunities to practice the techniques of turning.

Because they have played beforehand, the players can recognise the relevance of the work. They know where and how the different types of turn may help them in the game. This allows for more effective transfer back into game situations.

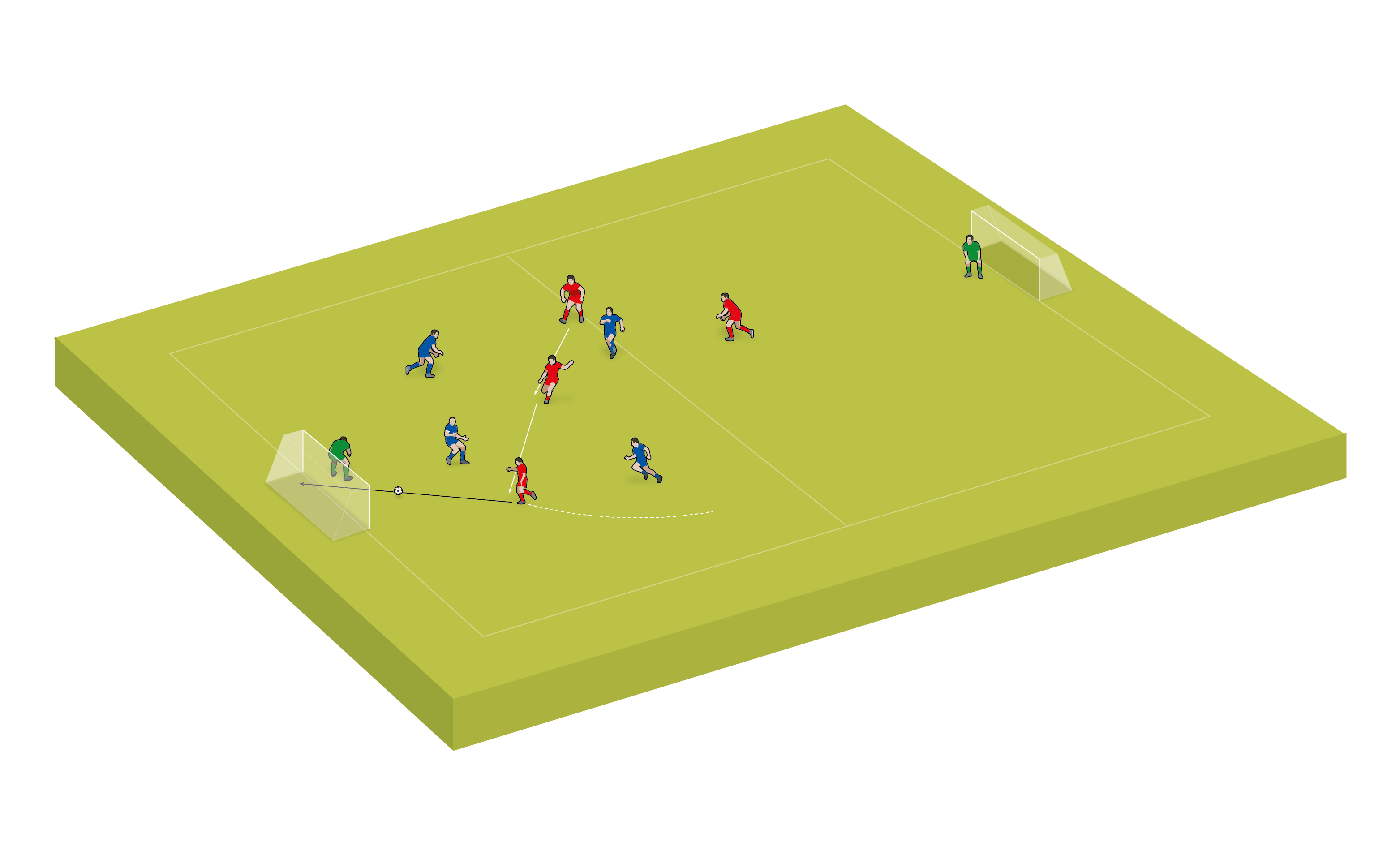

Part 3 - whole

Finally, the players play another game and revisit the original challenge, or modify it if the players are ready for things to be individualised or stepped up a level.

Using the whole-part-whole method not only helps players develop their technical prowess but also aids them to become more skilful in the long run. They are learning and practising not just how to do something, but when to attempt to do it in the game itself.

Conclusion

The truth about coaching is that it is complicated and a bit random. It depends on the players’ needs, their proficiency, the size and mood of the group, the culture of the club, the personality of the coach and, most importantly, the aim of the work.

How you coach depends on who you are teaching and what you are teaching them for. One size fits no one.

Understanding how players learn and some of the concepts behind learning and practice can go a long way to supporting coaches to do the best by their players.

Listen to this article in audio form

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Discover the simple way to become a more effective, more successful soccer coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Soccer Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use soccer drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of soccer coaching since we launched in 2007, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.