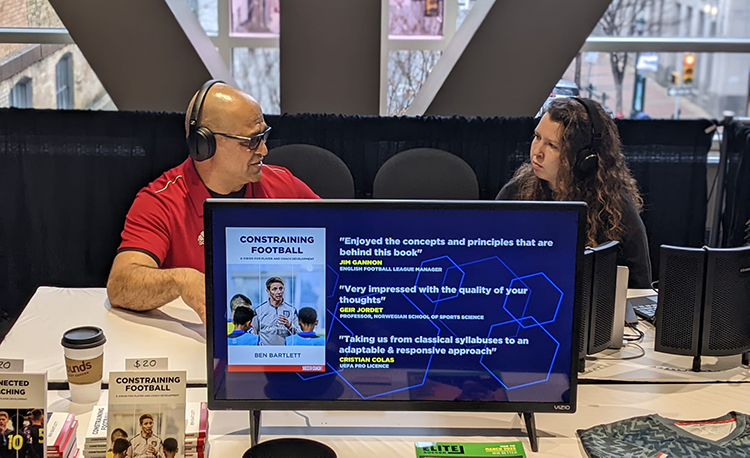

Dr Haroot Hakopian: Create a climate and define a team culture

High school girls’ coach Dr Haroot Hakopian tells Steph Fairbairn that handing over power to players and admitting you have messed up can pay off

Dr Haroot Hakopian got into coaching by accident when he suffered a significant knee injury - tearing his ACL, MCL and PCL - and requiring four different operations.

A move into coaching followed, alongside entering education. Thirty years later, he is still involved in, and loving, both worlds.

Dr Hakopian celebrated 20 years as an AP English teacher and girls’ soccer coach at Winston Churchill High School in Maryland last year. He also holds numerous other roles, including sitting on the United Soccer Coaches’ board of directors.

SCW caught up with him to talk about culture, climate, and the importance of telling your players when you’ve messed up…

SCW: What’s the difference between culture and climate?

HH: "Climate is a temporary thing. Let’s say a [college] freshman took a calculus test and absolutely bombed it. She’s in a horrible mood when she comes to training.

"That mood sets the climate. It’s temporary - it can last an hour, it can last a day.

"As a coach, you might notice that player spreading that negativity, or that there were five players in the same class that took that calculus test.

"You have to be in tune with external factors affecting the momentary climate of the team and address them - maybe joke around about how horrible you are at math.

"It requires you checking in with players real quick as they do their warm-ups - walk around and check the climate of the team.

"Consistent climate with a team establishes the culture. There is no agreed definition of culture, but the easiest way to explain it is the unwritten rules that lead to the way we do things, negative or positive.

"So using a personal example, a senior called Bianca - a phenomenal athlete, who worked her tail off to make the varsity team - tore her ACL in the second game and was out for the remainder of the season.

"The team rallied around her. They all made her cards, went to her house and delivered her favorite treats.

"That’s culture - it’s the way we do things. Not established rules or policies.

"Climate and culture are very closely related. If you don’t pay attention to a negative climate, eventually that becomes a negative culture.

“The climate is the coach’s responsibility. [In terms of] the culture, your job as a coach is to make yourself obsolete so even if you’re not there, it permeates everything you do.

“Your language as a coach is really important. I started figuring out positive things for the kids to say.

"I stole this from my dissertation advisor at Vanderbilt University. Whenever we made mistakes on anything - whether it was research or analysis - his immediate response was: ‘Do the next best thing’.

“So don’t worry about what just happened, do the next best thing. I used that with my team and they started repeating that to each other when somebody was making an error.

"Now you have a climate thing. A simple phrase permeating the culture and all the kids take it with them wherever they go."

SCW: How did you land on the culture and climate idea?

HH: "I joke that it was accidental genius! I started my doctorate at Vanderbilt in leadership and learning.

“A lot of that focused on leadership not being this amazing personality of a leader, but expanding who the leaders are.

"One of the greatest lines during that program was, ‘In order to be a really powerful person, you have to give up power, and then you get it back’.

“That was really interesting. I found that we talk a lot about climate and culture, but when I dug down and talked to some coaches I knew, they didn’t know the difference between those two things.

“It was fascinating to me because everybody was interested in improving both. They had the idea, intuitively, of taking care of your players [being] step number one. If you do that, you’re starting to build a good climate and culture.

“But the most interesting aspect is, when you make a mistake, what happens? What do you do? Do you ask your players to evaluate?

“When we’re with our team, it’s very hard to be self-reflective. You’re leading a group who are vastly different in personality and then you’re trying to evaluate and reflect - ’did I do this right? Did I do that right?’.

“We are very reluctant to stand up in front of players and be like, ‘I completely screwed that up. I’m sorry. Let’s fix it.’ That’s a really interesting aspect of climate and culture."

SCW: What are some examples of a coach admitting they’ve messed up? Is it, ‘I got this session wrong’ or ‘I spoke to you in the wrong way’?

HH: "Those are such fantastic examples because, intuitively, we can watch a session and be like, ‘That’s not going well’.

"I don’t think we’re embarrassed, I just think we don’t want to stop the players, pull them out of whatever zone they’re in and say, ‘This isn’t working and it’s my fault’.

“A lot of times we might design a session and the players’ skill level might not necessarily match what we’ve created.

"It’s tricky to stop the session and say ‘This isn’t working’, but not make the players feel as if they were responsible. That goes back to talking to the players.

“The other part of ‘I’m sorry about the way I spoke to you’...if you go to any soccer game - youth, high school, club, higher level - you tend to hear very loud corrections. You don’t tend to hear very loud praise.

“That’s something I’ve practiced personally. I go into a game with a goal for myself - If I’m going to do it loudly, where everybody can hear me, it’s going be a 2:1 ratio. If I have three times where I yell directions or corrected, then I have to have six times where I praise something.

“If it’s that ratio, they tend to remember the praise more than the negative comments. If it’s just the negative comments that’s what they internalize.

“In most cases, players know when they messed up. Depending on psychology, especially with female athletes, they tend to be so much more critical of themselves.

“It’s better if the critique is individual and the praise is in a group. They hear the praise over and over, and then you pull them aside and say, ‘You took too many touches on that last one. Let’s try to make that a little faster.’

“This is where it’s important to give the power to the players. Not all of them are comfortable with it and of course I’m still in a position of authority.

"But there are players that are starting to be more comfortable saying, ‘Hey, did you meet the 2:1 ratio goal?’. Now I have somebody that’s paying attention to that, I’m like, ‘That’s a great question. Let me pull out my notebook where I’m keeping track’. It’s making sure they realize the power they have to create the culture and the climate.”

SCW: Do you think sometimes we project onto our players? We say ‘They’ve lost, they must be so upset’, but actually it’s us...

HH: "That’s such a brilliant point. A lot of my players love the team aspect - the camaraderie, the culture and the climate - and I tend to remember games.

“I’m like, ‘do you remember what happened in that game?’. They’re like, ‘No, I remember going out for ice cream with the whole team afterwards.’

“A lot of the things we think they remember, because that’s the way we were as players, that’s not what they’re remembering. They’re remembering those experiences with their teammates.

"A lot of them recover from those [bad] things much faster than we do. And that goes back to the way we speak to them.

"If we keep laboring the point of the errors, we’re essentially forcing them to remember those things rather than being able to get over it very quickly.

“They’re naturally resilient. Sometimes, based on the way we behave, we take that resilience away from them."

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Discover the simple way to become a more effective, more successful soccer coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Soccer Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use soccer drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of soccer coaching since we launched in 2007, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.