Games-based method of skill development

Young players should be regularly exposed to situations that replicate matches to enhance their technical level and decision-making, writes John Allpress.

Learning to play soccer presents players with a wide array of challenges.

The ability of an individual to master these during training and matches depends on a variety of factors, but there is one constant that cannot be avoided: skilful play has to be regularly applied in realistic situations, under pressure, in a variety of circumstances.

Genetics may have a bearing on how proficient an individual can become, but, in the long term, the devotion to deliberate practice can be equally significant in determining the length and level of a player’s career.

To do this over a prolonged period, players must enjoy playing, practising and learning in equal measure.

Technical or games-based approach?

Traditional approaches to coaching players have assumed that technique must be taught and developed before playing the game.

Teaching techniques in isolation – for example, teaching players to turn with a ball, as opposed to them learning how to turn in a game – may be easier for the coach to control, but it does not require players to think about its relevance to matches, and therefore bears little resemblance to the skilful play required for success in the ebb and flow of a real game.

"Skilful play has to be regularly applied in realistic situations, under pressure..."

Over emphasis on technique has generally resulted in the production of players who possess inflexible techniques and poor decision-making capabilities.

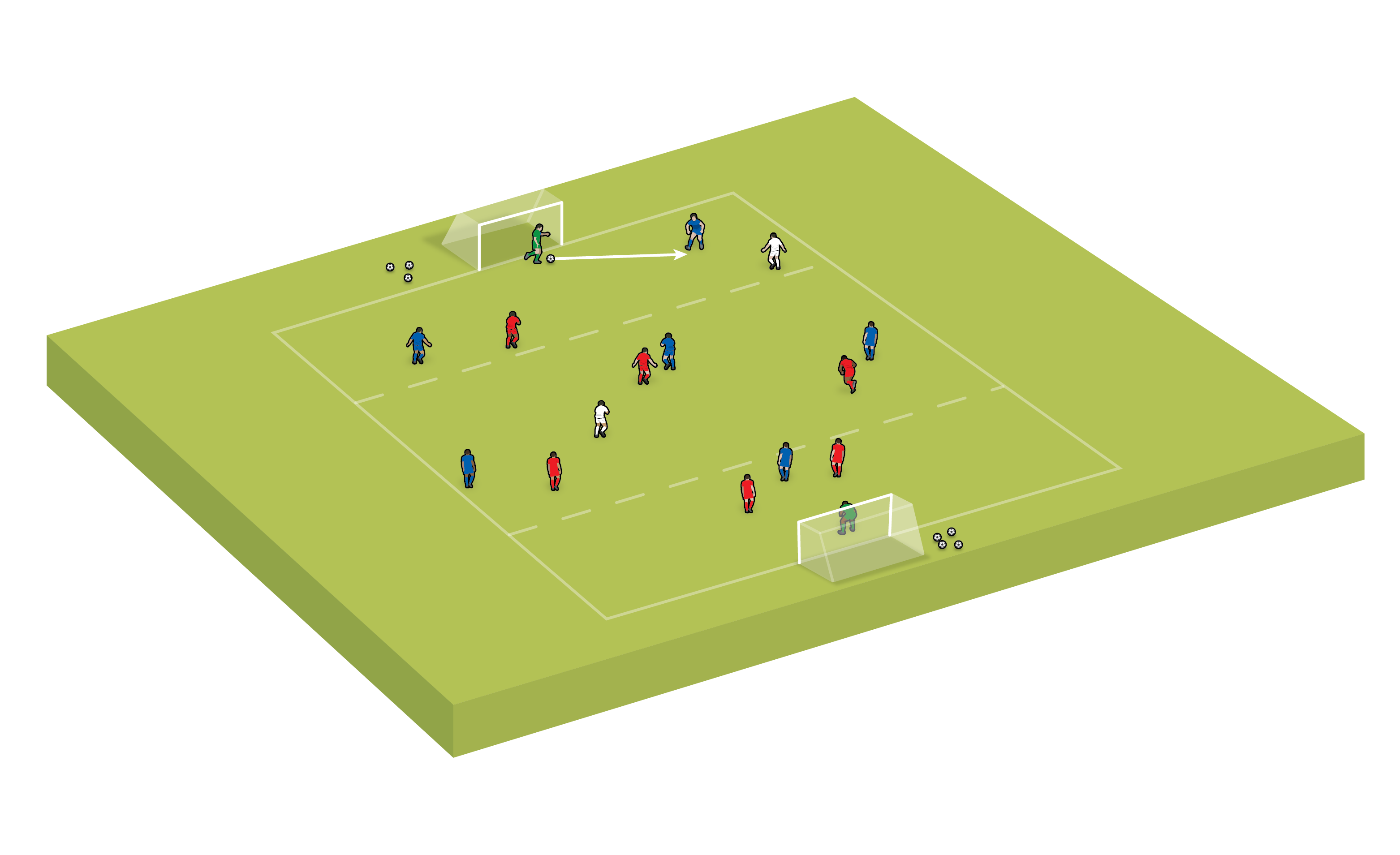

A game-related method for developing young players uses games and matchplay situations, where players are empowered through challenges to think technically and tactically, make decisions, solve problems and practice in the highly motivating environment the game produces.

It inserts learning to become more skilful – i.e. techniques and decision-making working in unison – within games or game-like situations, where players can make links to what they already know and can do, and positions deliberate practice and learning in an environment that is more interesting, challenging, varied, engaging and enjoyable.

The benefits of a games-based approach are centred around transfer of focused practice into the realities of the game.

Younger players have a much smaller library of experience than older ones. Starting with games-based practice helps them to see where a particular technical aspect fits into the overall picture.

It allows young players to link things to what they already know, or replace an old, redundant way of doing things with a new way of working, building associations and joining the dots.

A professional player with a large library of experience will quickly recognise an isolated technique, know where it fits, and can derive benefits from working in this way. For youngsters, it’s more problematic, making transference much harder.

Technical work is not learning how to play the game. The emphasis is on developing the nervous system, so that messages can be efficiently sent from the brain to the part of the body required to act.

This means it is still an important part of practice – particularly if, for example, a player is struggling to nail a technique in unopposed practice – but must be appropriately integrated alongside a games-based approach.

The right decision in a match may be that a player deftly controls the ball from their left to their right foot, turns away from an opponent using their right and then transfers the ball back to their left, to pass it accurately, along the floor, to a team-mate 15 yards away.

A player’s nervous system needs to learn how to do that and must be able to reproduce very similar actions regularly, on demand, under pressure. This means building the required skillset, which needs focused, deliberate practice over time.

From my perspective, the required skillset includes:

- Receiving to pass

- Receiving to shoot

- Receiving to turn

- Receiving to dribble

- Receiving to run with the ball

- Receiving the ball at varying heights and speeds

- Heading

- Tackling

The aim is for players to become two-footed and two-sided, as this adds to their ability to be unpredictable.

A games-based approach, integrated with technical work, gives players the best chance to develop all-round abilities and equip them for the rigours of the modern game.

Technical work is, therefore, not ignored; it is simply situated in a different place, in a training session, to allow practising players to have a much better idea of where the technique fits, because they can see its relevance to the context of the game.

This involves using the whole-part-whole method based on variable and random practice.

Whole-part-whole method

Variable practice occurs when a single class of skills is trained using the variations typically found in games and matches – for example, turning with the ball.

The practice has smart variations, specific to the game, appropriate for the players involved and with competitive challenges.

In the specific example of turning with the ball, you need an area appropriate for the size, age and ability of the group, with players working with one ball between two.

"A games-based approach can equip players for the rigours of the modern game..."

The constraint is no repeat pass – in other words, players can’t return the ball to the team-mate who gave it to them. The question is: How many touches do you need to turn?

Random practice occurs when different classes of skills are combined which stimulate the technical, tactical and decision-making challenges found in a game – e.g., free play.

These are called smart combinations, as they consider the technical, tactical and decision-making requirements of the game, the characteristics of the players involved and the competitive requirements of the challenge.

Again, in the example of turning with the ball, play a game within a rectangular area, with a goal placed centrally at either end, with offside enforced. If you have odd numbers, like 8v7, play with it, as that is more realistic than using a ’magic’ player.

The question is the same as before: How many touches do you need to turn?

The sequence of the work should be random-variable-random or whole-part-whole.

The variable part of the work should give individuals more chances to practice, because of the player-to-ball ratio, but the question or challenge should be the golden thread travelling throughout the work.

Related Files

Setting up a session

How you set up and coach a session is, first and foremost, very much dependent on who you are coaching and what you are coaching them for.

It’s always important for the coach to ask three basic questions before planning their work:

- Who are the players?

- What do they need?

- How can I help?

The answers to these questions should incorporate many factors, including:

- The age and ability of the players

- The mood you, and they, turn up in

- The size of the group

- The equipment and resources you have at your disposal

- The time allocated to you

- The weather

- Your club culture

- What you care about and hold to be true

- The aims and objectives of your season.

When it comes to time and resource allocation, the work of someone with an assistant coach and two hours at their disposal two or three times a week will look very different from someone who is working on their own with an hour available once a week. One size fits no-one.

Generally speaking, the more time I had at my disposal, the more likely I would be to include a technical session at the beginning of training, for at least half an hour, then slot into games-based work.

If I only had a one-hour training session once a week, I would concentrate on a games-based approach.

Both types of session would include a dynamic warm-up at the beginning and a cool down at the end, as illustrated below. All times are approximate to include review time before, in and after action.

Two-hour training session

Dynamic warm-up – 20 minutes

Technical work – 30 minutes

Whole game theme – 20 minutes

Part practice – 20 minutes

Whole game theme – 20 minutes

Cool down – 10 minutes

One-hour training session

Dynamic warm up – 15 minutes

Whole game theme – 15 minutes

Part practice – 10 minutes

Whole game theme – 15 minutes

Cool down – 5 minutes

Summary

Instilling a work and practice ethic in players is imperative in the development of skilful play. An understanding of the knowledge, knowhow and techniques required to become skilful is also fundamental to a successful outcome.

But, central to becoming an effective player is good decision-making; the best players make the best decisions more often.

A games-based approach, which encourages skilful play, supported by a detailed technical programme, will give young players the best chance of equipping themselves for the modern game.

A programme of experiences, ideas and other stimuli, associated with playing the game, should lead to the development of skilful play.

The coach has a vital role to play in these processes, by designing the right work and setting the right challenges.

The game is not the teacher. It simply provides the most effective learning vehicle for young players. You don’t get better by playing less.

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Discover the simple way to become a more effective, more successful soccer coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Soccer Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use soccer drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of soccer coaching since we launched in 2007, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.