Four-corner folly?

In his latest article, BEN BARTLETT discusses an integrated theory of learning as an alternative to the dominant models across English and world coaching...

Separation and separatist approaches are strongly engendered into society.

As coaches, it can be challenging for us to commit to, embody and further develop an integrated approach to both the development of our players and our own growth with such strong, historical and prevailing constraints upon our practice.

Academia can perpetuate this problem, when assessing its students’ ability to break down whatever is going to be explored into smaller, more examinable elements to enable a conclusion to be derived.

This can lead coaches who aspire to study coaching and sporting performance eliminating elements of any particular environment to enable a smaller part of that system to be studied and measured.

Possibly, this promotes and sustains the notion that separating a soccer team and its players into smaller parts enables us to effectively understand the wider eco-system.

This is problematic. As soon as we cut particular elements out of a tapestry, we create edges and seams that didn’t originally exist. When we attempt to piece them back together, we replace a connected, fluid, living body with a patchwork quilt of pieces.

For example, we can study physical output and measures how far a player has run, how much of that distance travelled was sprinting and what their fastest speed was. Physical trainers can pursue more distance, covered faster with greater top speeds.

"Separating human beings into the ’four-corner model’ is deeply divisive..."

These kind of performance enhancements can be alluring, seductive and perhaps even influential of behaviour.

But this kind of information requires contextualising. For example, a centre forward who manoeuvres opponents with physical contact - even small, subtle movements - may challenge opponents in ways that basic physical metrics may not identify.

In this situation, there is still a significant ‘load’ placed on the striker’s human systems to generate and manage the physical contact while outwitting opponents with clever movement, which perhaps aren’t considered in the separatist nature of data collection.

The same principle carries into what might be considered psychological challenges.

Being brave in possession, consistent from game to game, stoic when things are challenging and resilient when individual personality is not a natural social fit are all expensive investments that should be considered with all players and the environment each are a part of.

These are the reasons why separating human beings into ideas like English soccer’s ‘four-corner model’ - the technical, physical, social and psychological - is deeply divisive.

Developing players’ characteristics in these areas in isolation, or educating coaches for a distinct period (e.g. the psychological part of the curriculum), presents problems.

It is no better, as some prominent psychologists perpetuate, to imply that human beings are underpinned psychologically - i.e. that one element of our human system is more important than another - with our brain acting as ’CEO’, controlling our systems from the top down.

Humans are integrated, both within our own personal, individual system and within a wider social system - and soccer is a dynamic game which draws on all of our human systems and their connection to other human beings that exist within the environment.

Superficial separation and siloes should be superseded by synchronisation. This requires a different methodology, one which removes itself from the strong social conventions we have been educated within and rewarded for conforming to; where success in life is achieved through aligning ourselves with educational dogma, enabling us to navigate our way to a productive life.

Breaking from these conventions can be challenging, socially isolating and uncomfortable. However, uncovering and embracing alternative, novel and human-responsive approaches to player and coach development can be the significant (not marginal) gain, particularly in contexts where constraints on our resources relative to our competitors make it difficult to beat better-equipped peers at their own game.

Methodology is different from method. A method might be a pre-set syllabus or coaching tactic; methodology is perhaps more of an integration of everything we’ve come to understand about our people and what they value in their soccer environment.

There is utility in investing every pore of our being into drawing this understanding together into coherent coaching methods.

We aren’t a collection of corners conveniently colour co-ordinated. Our curriculum isn’t our environment; our environment and the people in it are our curriculum.

While practices and game days aren’t the only important elements of the experience we can build and share together, they are useful ways to articulate how this integrated approach can be considered.

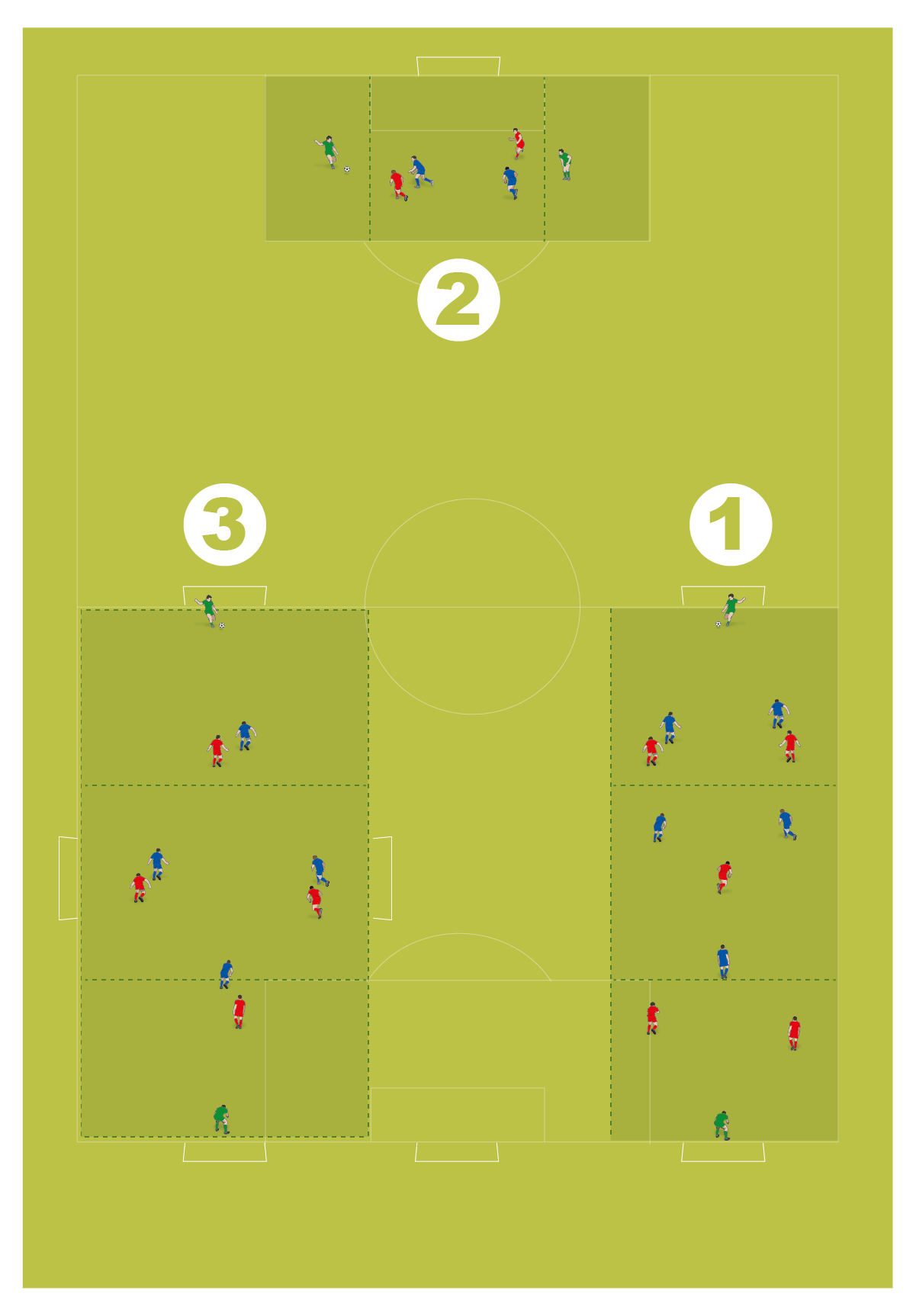

The three examples that follow on these pages can be perceived as being training practices - but every element of youth development is practice, even gameday. Hence, we can organise some variety into the games programme rather than follow a competition structure constrained with conventions created by committees.

These three examples could be organised across a number of consecutive training sessions, like a curriculum, and/or included as the competition formats for game day.

They have different numbers of players, a variety of pitch shapes and sizes, different types of goals and various ways to score.

Each of them is considerate of the entire human system, collectively. They intend to encapsulate what ‘four-corner’ aficionados might call the ‘red corner’ (technical and tactical), ‘yellow corner’ (physical), ‘green corner’ (psychological) and the ‘blue corner’ (social).

Additionally, these different games could be set up on a game-day.

Approach opponents and ask if they are interested in mixed game formats on certain days and challenge parents to referee the different types of games and conditions that the players are experiencing. This can aid their involvement, interest and depth of understanding.

The other adults in the environment are a key part of the technicolour that paints and enlivens our soccer landscape.

Parents, players and us coaches all sense, feel and are affected by the wonder and emotion that soccer brings to us all – the experiences we build and share can awaken the entirety of our nature, generating a reciprocity and connectedness between our enjoyment and our learning.

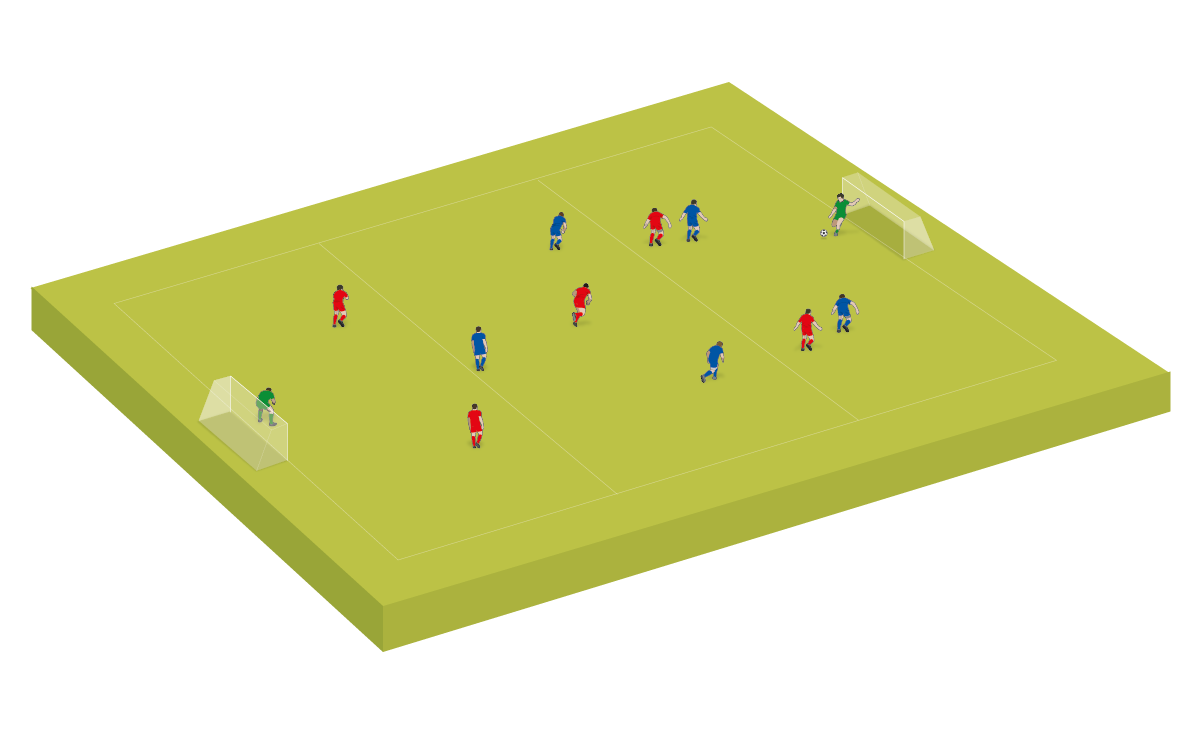

Practice 1 - In detail

- Every time ball goes out - restart with a corner. In possession: connect through all three thirds and score = 3 goals

- Defending: regain in final third and score = 2 goals.

- Question: what is your ‘special teams’ approach?

The pitch is narrow and split into horizontal thirds.

The set up of the players presents some varying problems to solve. The Blues have two Red attackers both defending and creating chances against their two defenders, while a Red midfielder is initially outnumbered.

Organisational constraints designed in this way can afford players the chance to practise in ways relevant to the situations that are present.

The Reds may build slower at times to attempt to draw a Blue midfielder higher and create space to play forward, or the Red goalkeeper may play longer into the front two to try to capitalise on the 2v2 high up the pitch.

The demands that constrain the game also encourage players to practise certain elements of it more than others.

In possession, if a team can play through all thirds and score it is rewarded with three goals. What gets rewarded gets repeated.

The Reds may then limit the times they play straight into their front two direct from the goalkeeper and find alternative ways to draw the Blues onto them - such that they can connect into midfield, perhaps encourage one of their centre forwards to drop deeper to balance numbers in midfield and/or use a patient goalkeeper to control the game as an extra possessor of the ball.

This build-up challenge is, conversely, contending with an out of possession reward. Regaining the ball back in the attacking third before scoring is rewarded with two goals.

Remember, what gets rewarded gets repeated. This can generate a competitive edge that separatists might believe exists in the ‘psychological corner’ - but it is better to consider the ways it influences humans across all integrated systems.

The perceived pressure and intensity such environmental, task and human constraints enable can influence and shape every ounce of our being, which has been shaped by genetics and environmental exposures.

The final task constraint within this game is that every time the ball leaves the pitch, play restarts with a corner.

Increasing the opportunity to practise set-plays, only restarting with kicks rather than throws and consequently encouraging some inventive short corner routines - perhaps additionally constrained by the pitch size - are some of the solutions the players are afforded the opportunity to experiment with.

It isn’t necessary to slow the game down or separate times the players can ‘explore’ (attempting novel game elements) from moments where they can ‘exploit’ (or perform successfully).

Competitive edge, exploration of new ideas and successful outcomes can co-exist. As can different ‘themes’.

Within this game, like in the unfettered game, players are focussing on building possession, pressing to regain and practising set plays; in unity, not as separate elements.

In previous curriculum iterations it might have been necessary to wait until the season was three months old before defending was included in the syllabus.

This is overly constraining. We can build experiences with and for the players that reflect the dynamic nature of soccer.

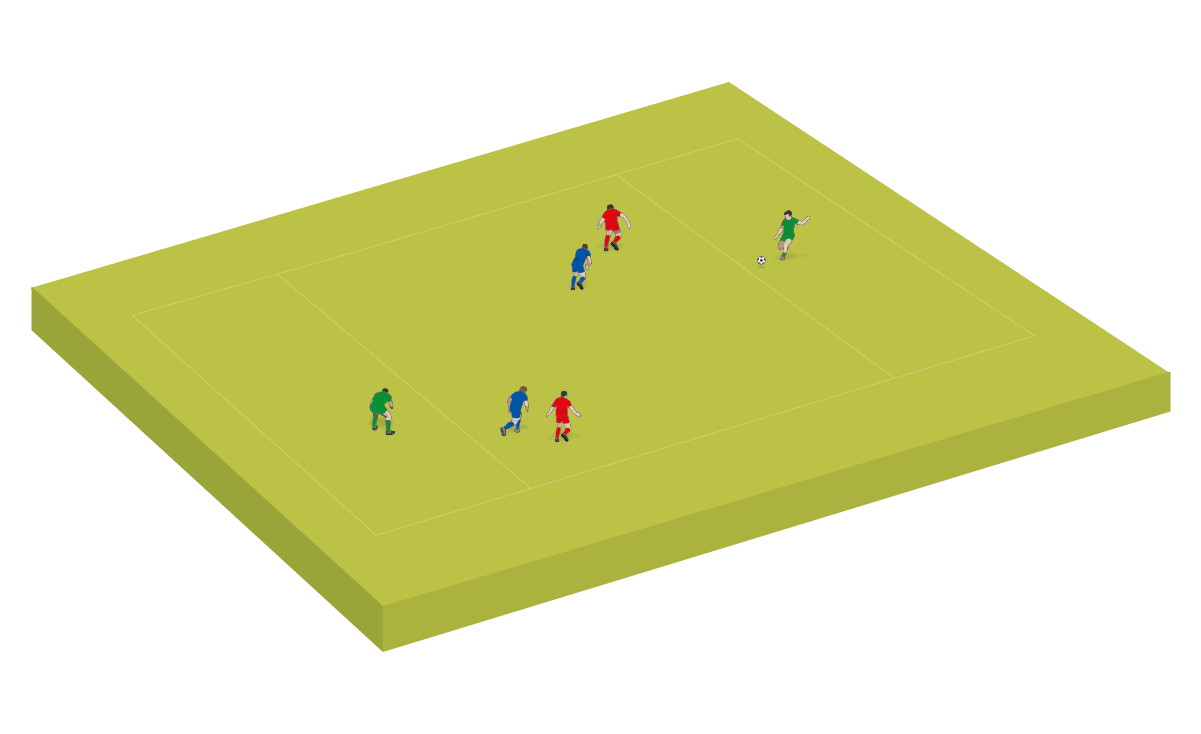

Practice 2 - In detail

Related Files

- Three-minute games. Longest streak of uninterrupted ‘end to ends’ wins the game. Winner stays on. Final two games: get a streak of five and score in big goal = win the game.

- In possession: combine centrally before playing to Pinks = 3 points added to streak. Defending: secure possession by finding an end player on regain (break their streak)

The principles of integrating our team intentions - rather than individual themes - with the nature and needs of the players across their connected human systems continues into the second game.

This is a smaller, 3v3 game. The goalkeepers’ only focus is on supporting play with their feet and being the target for the teams to play into to score.

The natural demarcations of the penalty box, which the players play across, provide the pitch boundaries, with the space from six-yard box to the side of the 18-yard box being the target area the players score by passing into.

If we have limited equipment or want to adapt on the fly in the moment, using such natural pitch boundaries can make this kind of transition time efficient.

The game is set up to last for three minutes each time we play, and we might play several times.

The winning team is the one who can move the ball from goalkeeper to goalkeeper, uninterrupted, the most times in each three-minute game. This affords the players the opportunity to focus on sustaining possession and building a winning streak.

Such constraints reward consistency and relentlessness while challenging the opposition to work hard to win back the ball, secure it safely on the regain to support them to break the opposition’s streak and build their own.

Across games, sessions and weeks, we may layer in some additional complexity. Combining with your teammate in the central area before playing to the goalkeeper in the target zone is rewarded with three being added on to their streak.

This can encourage players to play quick, clever combinations as well as receiving and playing directly forward to the goalkeepers.

Further, we increase the competitive temperature by challenging the teams that they will win and finish the game early by getting a ‘streak’ of five connections from end to end, before scoring into the goal that is naturally situated at the bottom of the penalty box.

This adds a ball striking or finishing element, as well as an aspect of urgency to defend the goal once the opposition get to a ‘streak’ of five.

These collective environmental, task and person constraints, again, elicit responses and behaviour from our entire being.

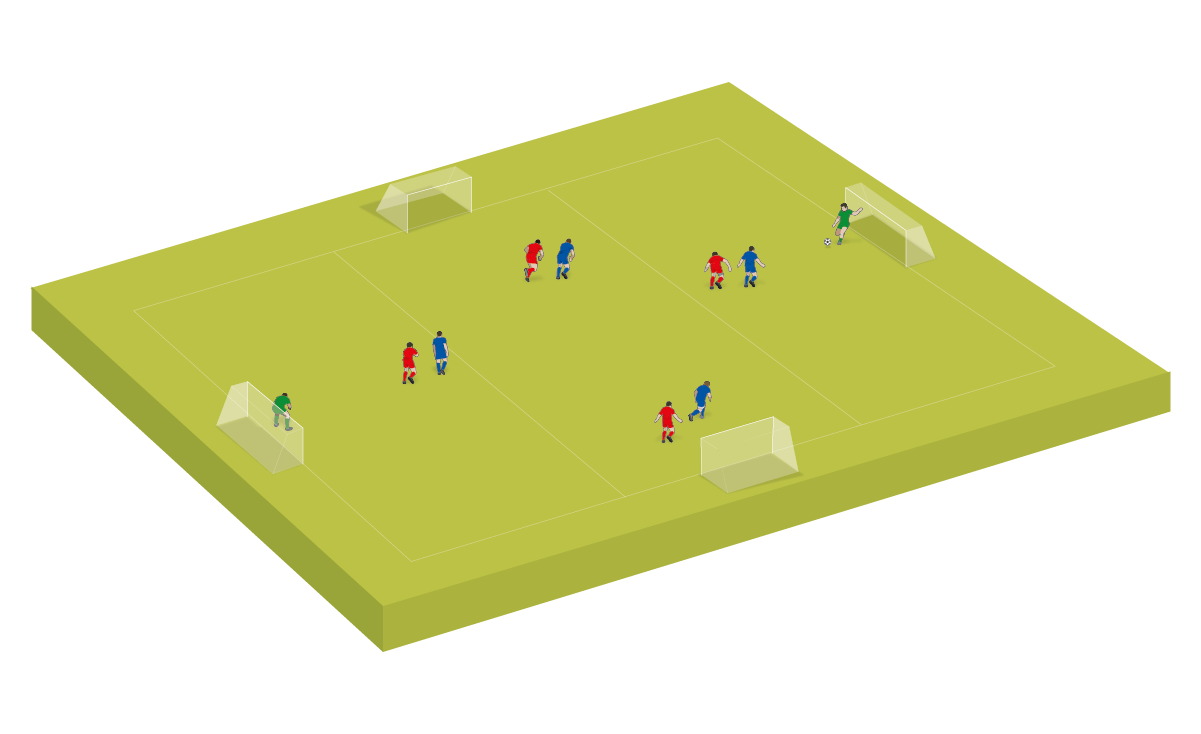

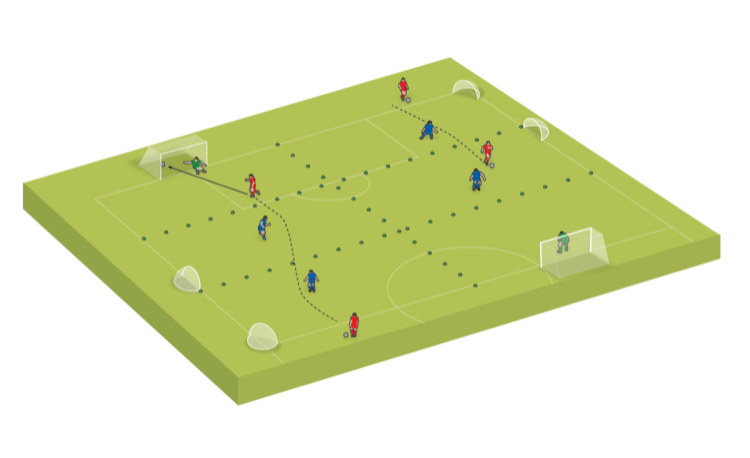

Practice 3 - In Detail

- In possession: with every goal scored, shift to playing in other direction (balance playing through vertically on a narrow pitch with playing across on a wide pitch).

The final game has four goals; however, at all times the game retains direction - with one team scoring in one goal and the other scoring in the goal at the opposite end.

This retains the natural laws of the game of soccer: two teams, two goals and one ball.

The pitch in this 5v5 game is long and narrow at the beginning. The whites attack the goal on the end line, the yellows the goal on the halfway line.

At the point that one team scores, the game shifts direction - with the goalkeepers moving to the smaller goals, perceptibly on the side of the original pitch. The game continues, albeit on a pitch that is short and wide.

The faster the goalkeepers and their team-mates can respond to the change that a goal initiates, the more likely they are to be prepared to take advantage of the switch.

The variance in goal size, and pitch shape and size, affords players the opportunity to practise building play and defending larger spaces vertically (up and down the longer, narrower pitch) before switching to practising using and stifling possession when there is more space horizontally (across the wider, shorter pitch).

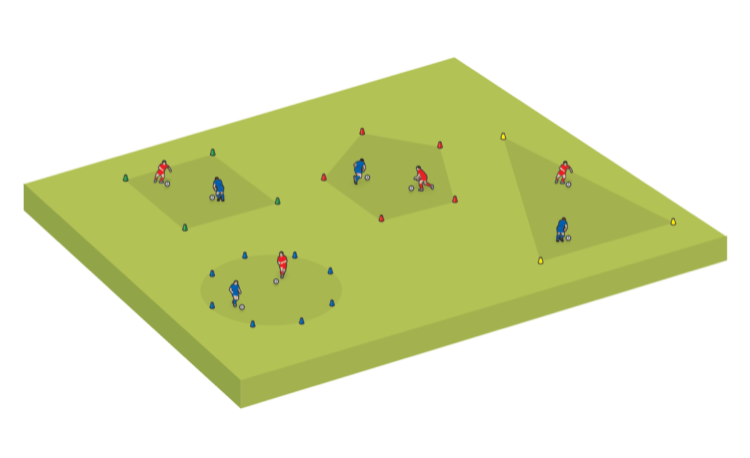

HOW THE PRACTICES CAN BE ORGANISED

This shows how you can organise these games so that different groups may play concurrently. Groups may be organised by age groups or by supporting players who may benefit from greater exposure to smaller numbered practices and increased number of ball contacts. Players might rotate each of the practices in one session or stay in the same game across multiple sessions or game days. There is no perfect science - just judgments based on what is important in your environment and to individual players. Explore different approaches and speak with the players about how they feel in different games.

Subscribe Today

Subscriber Testimonials

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Subscribe Today

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Subscribe Today

Discover the simple way to become a more effective, more successful soccer coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Soccer Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use soccer drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of soccer coaching since we launched in 2007, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.