Former Spurs academy coach's expert insights

Youth specialist John Allpress on the importance of playing with both feet, young players’ motivation to improve and the art of coaching decision-making.

John Allpress - the former assistant head of academy player and coach development at Tottenham Hotspur and ex-coach developer for the FA - recently joined us for a webinar.

He offered a terrific insight into how players learn, what they need and how that can better inform your coaching.

At the end of the webinar, John took questions from attendees. These are some of the highlights...

How do you encourage players to use both feet more - not only in their passing, but when they are running with the ball or dribbling?

JA: If you want to encourage people to do something, the biggest thing is the encouragement itself.

It’s about having their back 100%, because they are might feel they are not going to be good enough. They might think one foot’s not good enough, and the other foot is where they get their success or how they can show what they can do.

It’s about saying: ’We are a club that likes players to be two-footed and two-sided’. And it’s important to understand the difference between the two.

Two-footed is being able to kick the ball and produce things with both feet. Two-sided is being able to go both sides – left and right. This makes you unpredictable.

Then, once you have got the club culture and the encouragement right, it is about running practices where they have to use both feet.

If it’s a receiving practice and the ball’s coming to their right foot, get them to transfer it to their left foot or vice versa.

If you’re doing ’ball and a wall’ [passing a ball against a wall or between team-mates], do alternate feet, left and right. Get them to do five on their left, then five on their right.

Everything you do, talk about doing it with both feet. Even simple things like getting them to dribble through cones - get them to use both feet rather than one foot. You can have what we called ’wooden foot’ sessions, where they practice with their weaker foot.

Everything you do is then building into this process of saying: ’It’s a good thing to be as two-footed as you can be’.

Practising things in a two-footed way is important because it wakes up neural pathways. You’ve got exactly the same pathways on both sides of your body. It’s about making sure one is as awake as the other one.

Also, doing two-footed stuff means that you build up stability and strength on both sides. If I’m kicking the ball with my right foot, my stability comes from my left thigh and the groin area where you have got to be strong, because that’s your base.

What is the advantage of letting the players know that you are aware the upcoming match can be difficult? Is it not better to create a more upbeat, positive and motivational talk and environment?

JA: There’s nothing wrong with letting the players know the upcoming match will be difficult because they know already.

At Spurs, we played in a pre-season tournament against some other London clubs. One of these clubs beat our team 10-0. The lads weren’t very happy with that.

A while later, we were playing this same club in a cup competition. They are all sitting in the dressing room knowing it’s going to be tough.

What do I say? I can’t say anything other than ‘It’s going to be tough’ because they know it’s going to be tough.

We just said to them, in the usual way, ’We want you to try stuff. We’d rather that you made a mistake than not try it. We want you to go and have a go. We’re not worried about the result. What you’ve got to do is go out and do the best you can’.

You show that you know it’s going to be hard but you want them to go out and play. They won 5-0. Not that the result is everything.

It’s making sure that they know you know what’s going to happen. The positive environment comes from the honesty.

You’ve got to be yourself. If I go in there and start trying to spin them a yarn, they’ll know straight away. When I was a player, I knew when the manager was spinning me a yarn. Players know. They are not daft.

It is important to be honest; to tell them it like it is. This is especially true in elite environments like academies.

They need to know where they stand, what they have to do and what they have got to work on. Honesty comes to the fore, because you don’t do anyone any favours by sugar-coating things.

For young players, everything seems to need to be a competition to keep them motivated. How do you keep them focused through a session? Are there things you can change to find new motivators or should you keep things as competitive as possible?

JA: Kids that play sport are naturally competitive. It’s really about what the particular piece of work is about.

If it’s about trying to get a technique right, it’s up to the coach to create a practice where the focus is on the piece of work. That’s the challenge in itself.

Kids like the challenge. They like it to be tough. They don’t like things to be too easy.

I think competition is good. Kids like races and they like games where they are going for the biggest total. They like you to keep score. They like to play games.

It’s really important to understand that kids are competitive. But it’s up to you, as the coach, to focus them on different things.

You can tell them, for example: ‘For this bit, slow it down. This bit isn’t a race. It’s about getting this bit right’.

It might be punching the passes, or getting the technique of a turn right. It’s about the emphasis that you put on that.

But you can’t kill off competition. Competition is really good. Kids love it. Within that, it’s up to you to make sure you’re creating an environment which emphasises what you want to emphasise.

Soccer is a competitive game and players have to be able to produce their techniques in a competitive situation. They’ve got to be able to be skilful in a competitive situation. They have to be able to produce stuff under pressure. It’s that balance all the time.

Related Files

How can you build a culture where players want to get better and hold each other accountable? How do we motivate players to want to get better?

JA: Even in elite environments, although you might stress about the importance of getting better, not everybody is driven in the same way.

The ones that have a fighting chance [at making it] are the ones that are driven by mastery.

When kids go to academies, their prime directive isn’t actually to win matches for their club. It is to get better. If they get better, they will win more games.

The motivations come from them. I can’t make someone be motivated. They’ve got to be driven in their own way.

My art teacher couldn’t make me motivated to become a better drawer. That driver has to come from me.

"I can tell you what you have to do to become that player, but I can’t make you do it..."

What you do as a coach is provide the opportunities. When you coach people, you have to understand that the players in the group haven’t all got the same motivations.

The likelihood is, as players rise through the levels, the more likely it is they’ll have the same motivations as you.

But when players start out, and certainly in grassroots clubs, not all kids have the same motivation.

Some want to get better. Others just want to play with their mates. It’s important to understand that process and the fact it is driven by the player.

Once they can play soccer, that may be all they want to do. They may just want to turn up every Saturday or Sunday, play with their friends and then go home and have dinner.

These players aren’t driven by the same stuff as kids who really want to improve because they have a desire to be a pro or become a world champion.

The message is: if you want to be this player, these are the things you have to do to give yourself a fighting chance.

But I can’t make you do it. I can tell you what you have to do in order to become that player, but I can’t make you do it.

What are people accountable for? That’s another thing. What I used to say to my players was: ‘If I was the manager and I didn’t know who you were, what would I look for when I came and watched you play?’.

The answer is: enthusiasm. I’m looking at you and I’m thinking: ’Do you look like you want to be here? Are you running? Are you trying your best? Are you putting in a shift?’ That’s the key.

It’s important to understand the difference between asking people to do their best and try their best. I can’t guarantee to do my best, because the person that’s playing against me might be so good that I can’t do my best. But I can guarantee to try my best.

I can’t guarantee that we’ll win, but I can guarantee that I’ll put a shift in and my intent will be good. I’ll try to do the right thing.

You can make your players accountable for trying their best and being enthusiastic and running. To be a footballer, you have to run. That’s the most important thing. You can be as skilful as you like, but you’ve got to run.

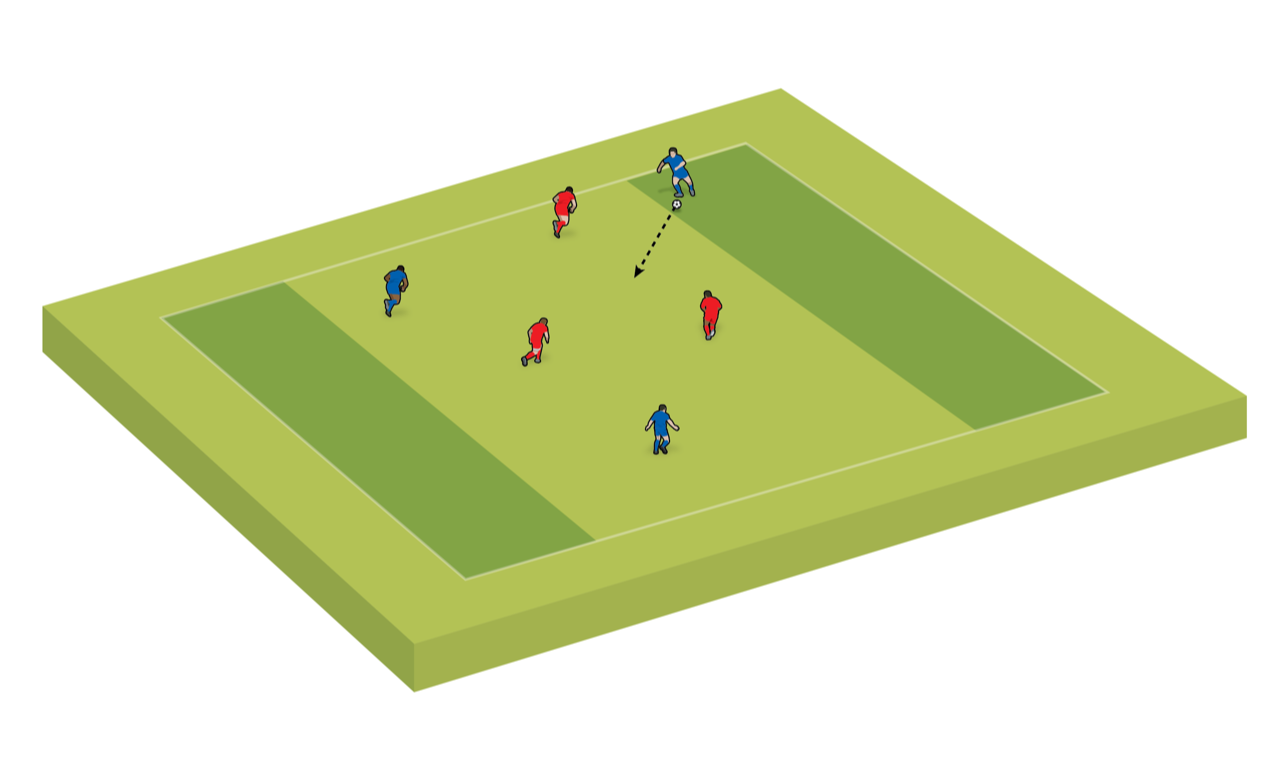

In the ’whole-part-whole’ training method, during the ’part’, do you prefer unopposed technique practice, opposed skill practice, or a combination of both?

JA: It depends on the players and their level. I think the key thing about the ’part’ element of the practice is it allows the players to have more goes.

Let’s take turning as the theme, as an example. When it comes to the practice, if you’re doing ’let the ball run across your body and try to play forward’, you have to create a practice where there are lots of opportunities for as many of the players as possible to practice that, going through that process.

If you’ve got a squad of 16, with four or five balls working, you can have little combinations going. A player can get their body ready to receive, let it run across them, then look up and look for somebody else. It’s all those processes that go on.

The key thing is that they have lots of goes in the ’part’ practice; lots of opportunities to practice what you’re working on. That’s what the part practice is for.

It can be opposed, it can be semi-opposed, it can be unopposed. The key thing is that they have lots of opportunities to practice it.

For example, the ’whole’ might be 9v9, then the ’part’ is 4v4s or 2v2s. We’re breaking it down into smaller numbers so they are having more opportunities to practise.

"If you’ve decided you want everyone to play, establish that before you start the season..."

If you are losing all your games, but know you could win them with your best players on the pitch, should you play your best team for a few games to get confidence up?

JA: Firstly, what sort of team are you? Is it just one team or Is it part of a bigger club?

All of these things should be established at the start, so that when you have a meeting with the parents at the beginning of the season, you can tell them about the culture you want to create.

You can talk them through what you believe in, what you hold to be true and what you care about. Then the parents can either say: ‘No, that’s not what we want’ or ‘Yes, that’s what we want’.

If you’ve decided that you want everyone to play, you’re not worried about the results and you want everybody to enjoy it, establish that before you start the season.

I used to use this approach when I was a school teacher. I’d sit down and pick my best team - and that team never played. I would put other people in.

It’s hard if you end up having all your weaker players playing at the same time, because your weak players need the stronger ones to help them.

You need to plan beforehand so that if you play three in midfield, for example, two of them should be strong [in ability]. Then the weaker one has got a fighting chance.

If it’s part of your process that everybody plays, make sure you have a good number of your strong ones on the pitch at the same time, rather than all of them.

The other thing is that kids have to learn how to come on as a substitute. Even your best player has to learn to come on as a sub, because they might leave to play for a better team and end up on the bench.

It also comes down to culture, again. Kids want it to be fair. If they’re joining a club, they want to play. They don’t want to be a sub every week. So you’ve got to sensibly balance it out to make sure that everyone gets time on the pitch.

Pick your best team - and then the best team never plays.

How do you coach decision-making?

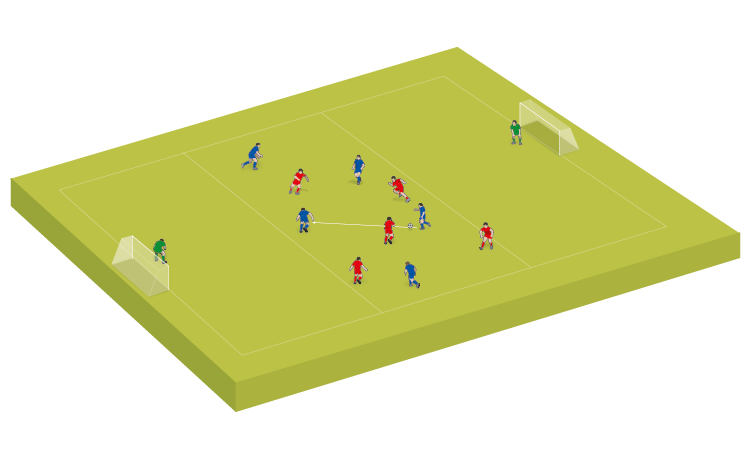

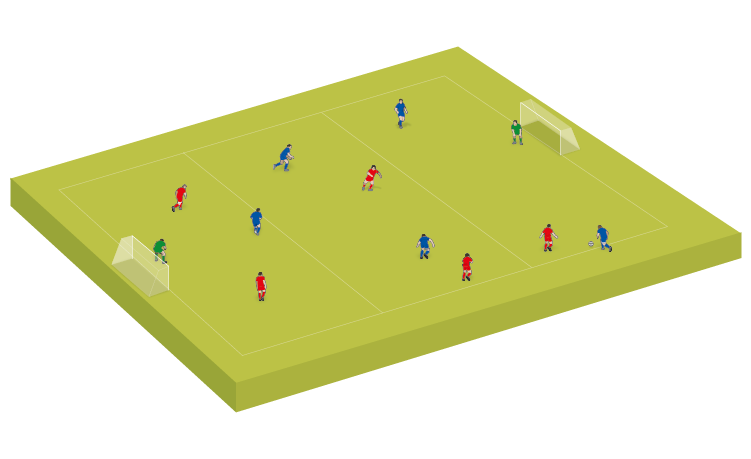

JA: You play soccer. Decision-making is knowing what to do when and the only way to coach it is by playing and then going, ‘Okay, what were you thinking when you tried that?’.

The only way to learn how to make decisions in an environment where nothing ever happens in exactly the same way, but lots of very similar things happen a lot, is to play within that environment, make decisions and make mistakes, and have your coach on the side let you try stuff.

The only way to learn how to make the right decision is to work it out. And you’ve got to accept that some kids are better decision-makers than others.

Play a proper game, with offside and central goals on a rectangular pitch, because that’s soccer. Play 9v9, 2v2, 4v4, whatever; there are always decisions to be made.

If you want them to make more decisions and get more of the ball then play smaller-sided games. But play proper games - so even in the 2v2, have offside and the goals placed centrally.

Besides reassurance and positive feedback, do you have advice for comforting a player who is down on how they are playing in a game?

JA: I think it’s important to be honest. If a player isn’t doing very well, they know they are not doing very well.

If people make mistakes, how you word things is important. I used to use things like: ‘Try and get back into credit.’ So, if they’ve made some mistakes, they should try and make the next pass, header or tackle a good one.

It is important not to take people off. If they feel they are struggling, don’t take them off.

Often, if a player is playing badly, they feel they are going to get taken off. But everyone has bad games every so often. They might be trying to do things that are just a little bit outside of their comfort zone.

If we’re practising staying compact and pressing in training, for example, that will be the challenge we set for players in a match. But once you’re up against someone who’s got a different coloured shirt on, the tariff for mistakes goes up.

That’s when players really need you to be backing them 100%. Your body language has got to be really good on the side. The substitutes watch you; everybody watches you.

The most important person in a player’s football life is the one that picks a team. They look at you no matter if it’s grassroots, top academies or senior first teams.

There are three questions that you ask when you are approaching every session. What are they?

JA: Who are the players? What do they need? How can I help?

Ask those three questions every time. And sometimes the best way you can help is just by leaving them alone to get on with it.

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Discover the simple way to become a more effective, more successful soccer coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Soccer Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use soccer drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of soccer coaching since we launched in 2007, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.