Developing soccer skills: Covering and recovering

If a defender goes to close down an attacker, a team-mate must fill in. Moritz Kossmann explains to Steph Fairbairn what’s required to make it happen.

Moritz Kossmann is DStv Diski Challenge coach and head of youth at Cape Town City in South Africa.

Here, he speaks to Soccer Coach Weekly about the skills of covering and recovering – how the approach to them differs depending on position, how we sell the skills as positive actions and the role leadership and communication plays...

SCW: How does covering and recovering differ depending on the position you play or where you might be on the pitch?

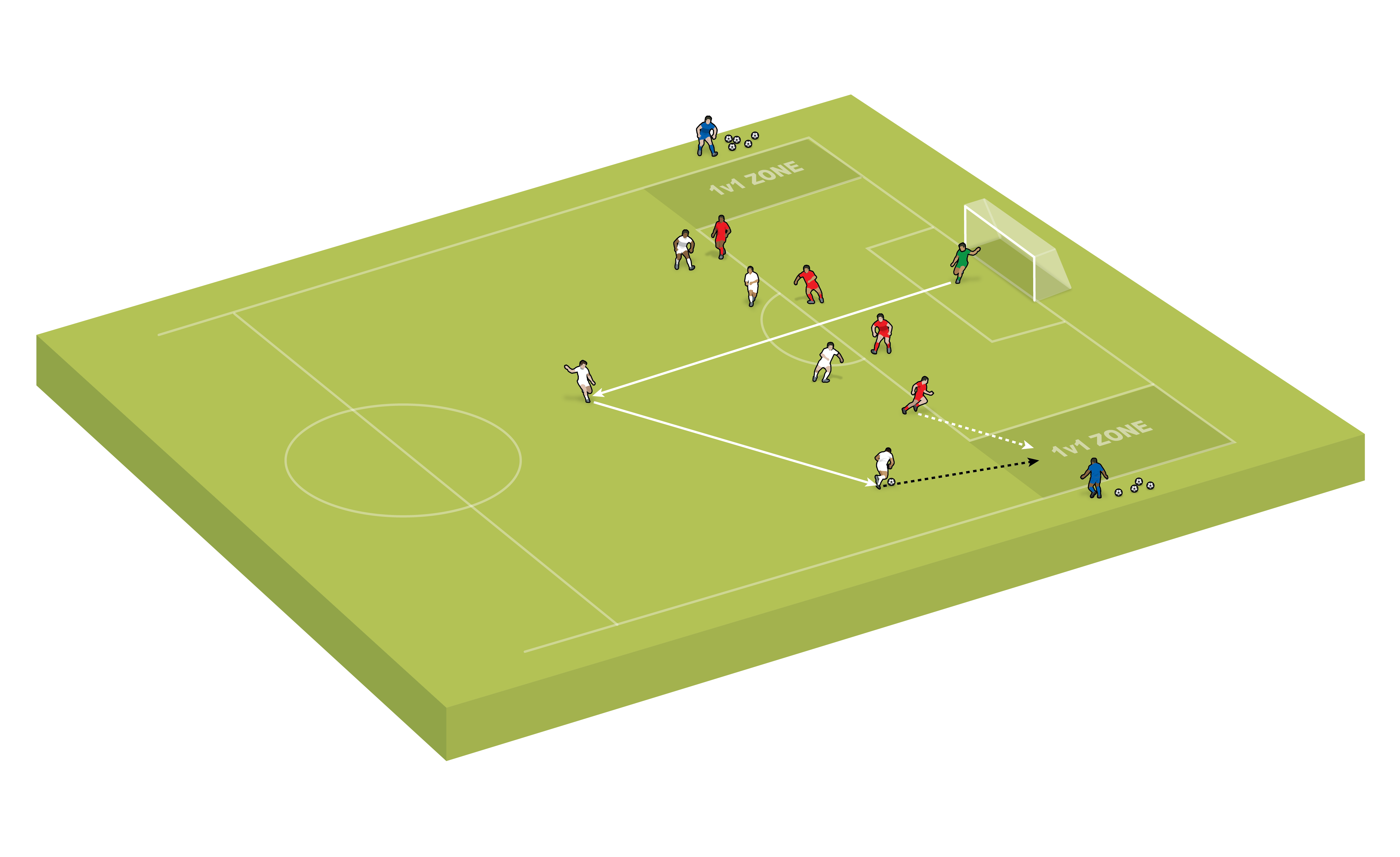

MK: [Let’s] assume that we are playing in a back four. The opponent has the ball on the wing and our full-back decides to go out and press this player.

As a starting point, the full-back might be slightly further inside, in an area which we could call the half space. But now, because they are trying to win the ball, they go out to the wing, closing the ball down and pressing.

If that was done with only one player, there would be a hole in the back four that perhaps the opponent could utilise.

To make sure we are covering all the most dangerous spaces on the field, what would typically happen is that our centre-back would shift into the original position of the full-back and the other centre-back would shift into the position of the centre-back who is covering. Then the full-back on the far side would shift into the [original] position of the centre-back on the other side.

So you have this chain reaction when the ball is on the flank, trying to cover the ball side and the centre of the field, leaving the far side open.

If it is happening in the centre, it would perhaps involve a centre-back stepping out to press a player. Now, the full-back and the other centre-back shift closer behind to close the pocket of space where the player started their pressing action.

We are always looking to cover the spaces close to the ball and spaces in the centre. A covering action is really an enabling action for the player [nearest] the ball to press with freedom.

In our hypothetical example, where the full-back stepped out onto the wing, [if] the other players aren’t covering them and they get beaten, the opponent attacks the space this player has vacated.

And now, the next time you have to go out and press, you’re going to think twice about it. You’re not going to be as aggressive or take a risk to win the ball because you’re scared of the consequence of getting beaten by the opponent.

Covering enables pressing. At a high level they can only happen together, because when we press in a high level of soccer, it’s often not the first player who is going to win the ball. It might not even be the second player.

It might be that the third player, who is initially covering in an attempt to maintain pressing, becomes the winner of the ball because of a chain reaction of rushing the opponent for space and time. Their actions get worse until eventually we win the ball.

Covering is almost an insurance policy for pressing: making sure that we can take a risk and we are not immediately exposed for it.

Recovering is what happens when a player has been beaten. As a hypothetical example, [let’s say] our striker presses the opponent’s centre back - but, because they are slightly late in their action, the centre-back manages to beat them and get goal-side of them.

I think we can generally define a player being beaten and needing to recover as when the opponent gets goal-side of them.

Now, what does our player do? Are they going to stay high up the pitch and say, ‘Okay, I did my pressing action. It was unsuccessful, so now I start slow jogging or walking’?

What we want is a player that gets beaten but makes another pressing action and perhaps even another after that. We’re looking for a general high level of activity when defending.

SCW: What are some of the basic principles we might start with for younger players around covering and recovering?

MK: The German language has a very popular word in coaching - ’Tiefenstaffelung’. Essentially what it means is that you are staggered when defending the depth.

If we consider two players defending together, we don’t want the pressing player and the player not pressing in the same horizontal line, because one pass into the gap beats both to a goal-side position.

This ’Tiefenstaffelung’ word refers to the player not pressing being lower, horizontally, than the player who is pressing the ball. Now, it is much harder for the opponent to play a pass into the gap.

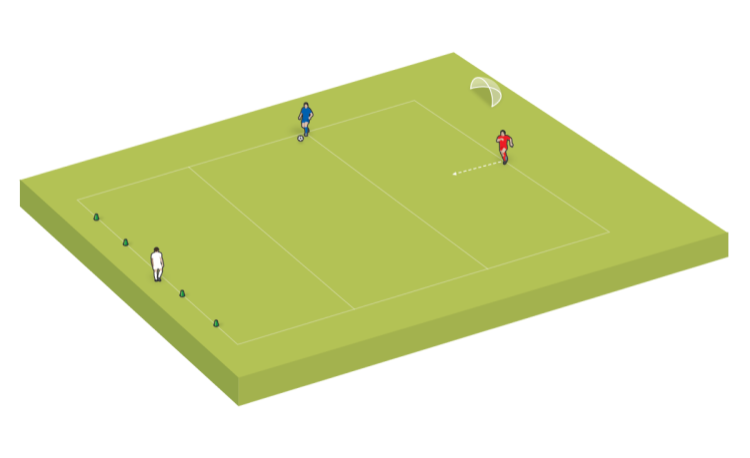

A great starting point to teach covering, and also recovery, is a 2v2 where you are teaching the player pressing the ball to do it without fear. The player that is not pressing should get into a lower horizontal position.

"Covering is almost an insurance policy for pressing - making sure we can take a risk..."

Now, if the opponent plays a square ball, that [covering] player might go out and press and the player who was previously pressing now recovers into a covering position. This is a really nice way to start.

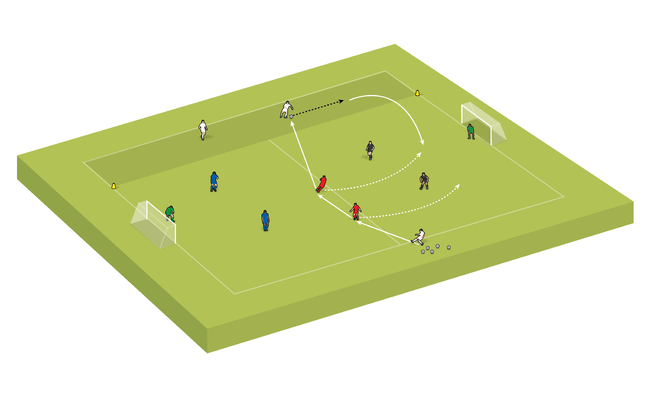

A nice rule in a Rondo, in a 5v2, is that defenders don’t allow the opponent to pass between them. You could say it’s an extra round in the middle in a rondo if the opponent manages to split a pass between the two defenders who are closing the ball.

The 2v2 is the starting point of teaching covering and recovery. It can be done from a very young age because it’s a game situation that is quite easy to oversee.

You have a limited amount of references compared to a bigger game. This means that the tasks you have to perform are going to be slightly easier and more straightforward.

SCW: Younger players, or those new to the game, naturally want to chase the ball. Sitting in the right space and covering isn’t the most glamorous action. How do we sell it as a more positive action?

MK: You have to ask questions along the lines of risk versus reward. What is the risk of both [defenders] going extremely high, relative to the reward? How much more of a chance do we have to win the ball?

Obviously, situationally, there might be moments where it makes sense to close the ball down with two players. But defending, just like attacking, is always a balancing act.

You are always trying to balance not conceding goals with trying to win the ball back - and, on the other side, you are trying to balance scoring goals with not losing the ball.

Making players aware of this balancing act - valuing the protection aspect while also trying to encourage them to be on the front foot to win the ball back - is really key.

The best way to do that, perhaps, is by showing them different situations and then asking questions that make them reflect about risk versus reward.

Related Files

SCW: When it comes to covering, how important is leadership and communication on the pitch?

MK: I think it’s crucial. That’s where a coach comes in. If we are coaching the whole time in our training sessions, and there are no periods where we quietly observe, then we don’t get players that talk a lot. The coach is doing all the talking.

It’s really key that we allow players to discover a concept through the training we have created.

Then we coach them more actively to see how we can help them improve and can take a step back to observe how they are using it independently of us.

In terms of who needs to communicate in what moment [on the pitch], a good general rule is that those players behind the other players should generally be more vocal because they have a bigger picture of the field. They can see more of the overall picture.

So, a goalkeeper should be someone that talks a lot, [as should] a centre-back. The far-side full-back, when the ball is on the wing, should be very actively communicating.

Having this rule that the players further from the ball, who can see more of the overall picture, more actively talk helps to ensure that these players are actively participating in the game and are helping the players closer to the ball.

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Discover the simple way to become a more effective, more successful soccer coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Soccer Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use soccer drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of soccer coaching since we launched in 2007, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.