A soccer coach's guide to interventions

John Allpress, formerly of Tottenham Hotspur and the Football Association, takes a deep dive into the delicate art of stepping in during training or matches.

The soccer world is awash with knowledge and information, much of which is reliable and useful – but some is definitely not.

Those of us involved in coaching and teaching the game need to be able to sift out the important from the trivial and the reliable from the disreputable. We need to know, clearly, what information we need to impart to players and when, and what to leave them to sort out for themselves.

Interventions are actions undertaken to improve a situation, either in training or on a matchday, for the whole group, or individuals within it.

These interventions must contribute positively to the players’ learning and practice environment.

Players should always feel that their coach has their back and their best interests at heart. This builds trust, which is crucial if learning and effective deliberate practice is to take place. Good interventions are central to this process.

In soccer, nothing ever happens in exactly the same way more than once – but many very similar things happen a lot.

So, basing your coaching on the premise that there is only one right way to do things is a bit problematic.

"Interventions must contribute positively to players’ learning and environment..."

There are various ways coaches can intervene in order to support their players.

Types of intervention

Interventions are the simple thing done well and can be achieved in two ways: by showing or speaking.

Showing

Showing can be done through analysis and videos, but most of the time it is carried out via demonstration on the pitch during training, or in breaks in play on matchdays, to illustrate technical or tactical aspects of the game.

Demonstrations can be a very useful tool in helping the coach to illustrate the focus of the work the players are undertaking.

It is important that the coach understands the impact of demonstrations and the language used to accompany them.

A demonstration will often be supported by a verbal explanation, which should help to clarify what is being shown and taught.

The way you speak and the language you use in large part contributes to the mood music you want to set, creating the learning and practice environment for the players.

Demonstrations should be clear, simple, show an accurate example and be achievable for the players.

They should act as guidelines, not absolutes, and the coach should prepare carefully for their deployment. Here are some ways to do this:

1. Think about your audience

When demonstrating to younger players, be particularly aware of the speed at which actions are performed, relative to the age group you are working with.

For example, consider the range over which passes are hit. A 30-yard diagonal pass may be achievable for an adult, but most 12-year-olds find it quite a challenge.

2. Consider who does the demonstration

Adults can often make things that youngsters find difficult look easy. Other young players in the group can, therefore, be used to show good practice.

If there is a player in your group who you know can execute what you are looking for, and they are open to demonstrating, don’t be afraid to ask them to do so.

3. Think about where the players are positioned

A picture may be worth a thousand words – but where players observe from is very important, too.

A different viewing angle may well give off an entirely different impression of how to execute an action.

For the demonstration to be effective, players need to know what they should be looking for – and looking at – to ensure they see things from the same point of view as the coach.

4. Link the demonstration to the game

Players should also appreciate the purpose of the action, so they can put it into some sort of context.

Link the action to an expectation as to how it can be used effectively in a practice or match situation.

"A 30-yard pass may be achievable for adults but 12-year-olds may find it a challenge..."

5. Encourage players to do what has been demonstrated

With humans, if you simply tell them something they will forget it; if you show them, they will remember it; but if you get them to do it, they are more likely to understand what is being asked of them and be able to put it into practice at a later date.

Consider how you can get players to repeat the demonstration there and then, or do it shortly after in a game situation.

Speaking

A coach’s spoken interventions can be executed in a variety of ways, using various different tools.

Coaching is a subtle art, multifaceted and dependent on what you are coaching, the age and proficiency of the players, the size and the mood of the group, the weather, the ethos of the club, the personality of the coach, what they care about and hold to be true and, most importantly, the purpose and overall aims of the coaching.

How you coach depends on who you are coaching and what you are coaching them for.

So, each of the following tools should be chosen each time, dependent on the above factors.

1. Direct instruction

Telling players what to do and how to do it. This often boils things down to right and wrong.

2. Asking questions

Using ’What?’ questions allows the coach to gain more information. For example: ’What’s stopping you?’; ’What if you could...?’; ’What if you did that?’.

Using ’How?’ questions allows the coach to dig deeper. For instance: ’How can you see what to do next?’, or ’How many touches do you need to turn?’.

3. Prompting then active listening

This enables the coach to redirect the focus, if necessary, then prompt and probe for accuracy or detail.

For example: ’In this situation, what would you try?’, then: ’How would that help you and the unit [or team]?’.

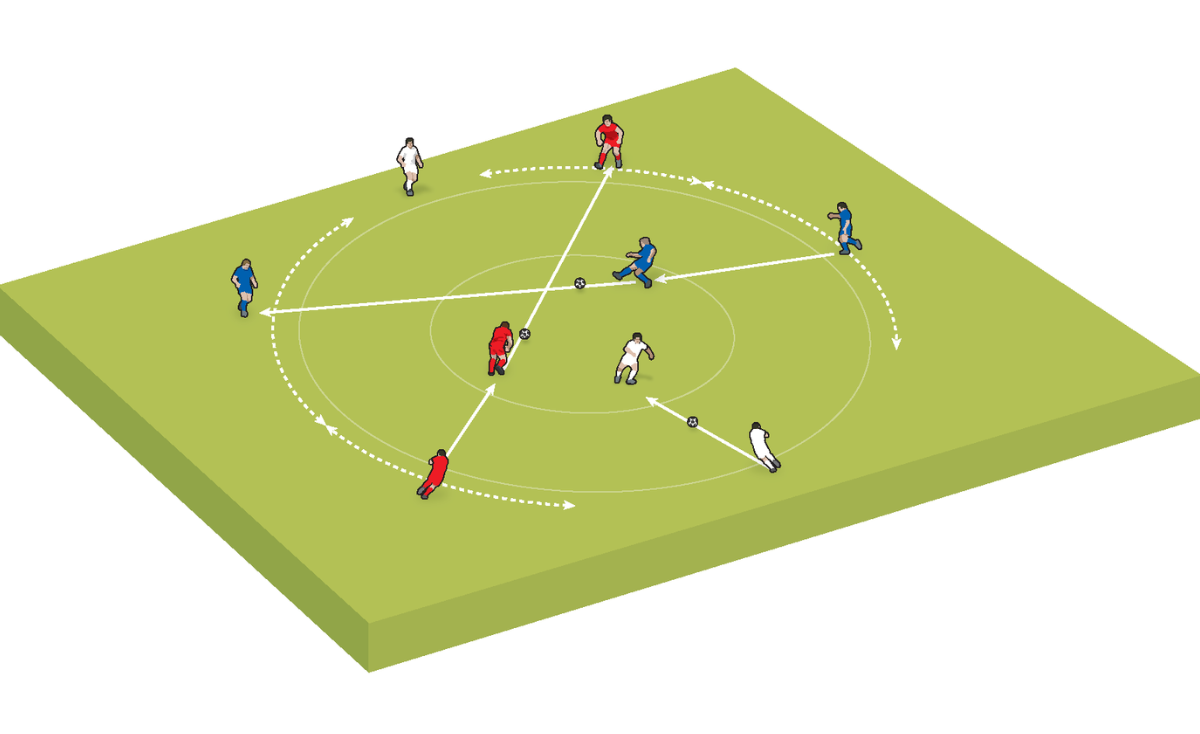

4. Conditions and constraints

These allow the coach to focus individuals, units and groups, letting them concentrate on a particular aspect of play to enhance techniques during free play or practice.

Examples could include ‘no repeat pass’, which means a player can’t give the ball back to the person who gave it to them, encouraging third-player participation, or ‘you can’t pass the ball backwards twice in succession’, to encourage forward play.

5. Challenges

These enable the coach to encourage skilful play, as they do not compromise decision-making during the practice or game.

Examples of this include: ‘Look for opportunities to pass the ball forward off one or two touches’, or: ‘Try to let the ball run across your body and play forward as a first action’.

The language is important here. It should never imply that a player must do something, but should simply suggest that they look for the right time to execute the action, thus enhancing their decision-making and the techniques required to make it happen.

Challenges and questions can also be used together to further prompt learning. For example: ‘Work out when it is best to mark on the inside or outside shoulder. Which side helps you to intercept and set up counter-attacks?’.

The challenge and question can be delivered at the same time, or paced through the session. You may offer the challenge, see how a player gets on, and then add in the question to encourage them to think about it more.

6. Don’t speak at all

Also known as ‘skilful neglect’, this is when the coach backs off the players, letting individuals, units and the group take more responsibility for their own learning and practice, which gives them the space and time to work without interruption and interference.

Related Files

Working with individuals and units

It is important to realise that all of the coaching tools detailed above can be used to help the group as a whole, units within the group, or individuals within units.

This allows us to tailor our coaching to specific group, unit, or individual needs.

As an example, three midfield players could all be given different tasks depending on their needs:

- Player 1 – Challenge: try to let the ball run across your body and play forward as a first action.

- Player 2 – Constraint: no repeat pass.

- Player 3 – Constraint: maximum two-touch football. Players can also be given the same task, but have it presented in different ways, based on how they like to engage and learn. For example, the defensive unit could be set up in the following ways.

"Challenges and questions can be used together to further prompt learning..."

- Right full-back – Challenge: look for opportunities to pass the ball forward off one and two touches.

- Right centre-back – Question: how many touches do you need to pass the ball quickly into your midfield players?

- Left centre-back – Challenge: work out when it’s best to pass the ball into your midfield players or run with the ball.

- Left full-back – Question: how does the pass you receive from your team-mates help you pass forward quickly into your midfield players?

The action-review process

An action-review process is a way of reviewing if the aims and objectives of a session, match or period of work are being met, and, if not, allowing us to better support them to be met.

Interventions can play a key part in the overall action-review process.

Before-action reviews

The action-review process can be used effectively in training and on matchdays as it sets the targets for individuals, units and the group.

On a matchday, the before-action review can take the form of a meeting to go over any match aims and objectives. In training, it can set the purpose and focus of the work and can be either technical or tactical in nature.

For example, you could set a condition such as ‘play with a maximum of two touches’, or a challenge like ‘think about how we can dominate possession in the middle of the team’.

In-action reviews

In-action reviews begin once play is underway and are linked with the overall purpose of the work. They can be both informal and formal.

An informal in-action review can simply be encouragement, like a ‘fly-by’ pat on the back, accompanied by a quiet ‘well done, that was a really good pass, really well-timed’.

One of the main advantages of in-action reviews is that they are really good for catching players doing things well.

Note the specific point about the timing at the end, allowing a player to understand what was good about what they did.

A formal in-action review is when the coach stops play to highlight an aspect associated with the overall focus and purpose of the work.

This is most useful when it points out good play, as players get a positive picture of what is required for success.

After-action reviews

After-action reviews are a method of evaluation. They aim to capture learning from the players’ practice and promote success for the future.

They are most effective when collaborative, and centred on discussion and sharing ideas.

The ability of the coach to ask good questions, then listen and acknowledge the answers, really helps to check players’ understanding.

Too often, the after-action review becomes a monologue, where the coach simply ticks off points they want to raise with the players.

It is important the players focus on what happened, rather than what they would like to have happened.

A good after-action review will help them distil what went well, what could be better and what needs to be done to improve things.

After-action reviews on matchdays can be tricky. Emotions can be running high, whether the team has won, drawn or lost.

If the coach wants to review the individual and team performance successfully, judging the mood is very important.

The coach, who knows the players better than anyone, should make the call. Then post-match discussions can be handled accordingly, and may even be left until the next training session.

Summary

Coaches constantly face the complex task of balancing structure and organisation with choice and freedom of expression.

The right balance creates an optimal environment for that mysterious and elusive process we call ‘learning’ to take place.

Using interventions, and using them well, can go a long way to enhancing player learning and progression.

JOHN’S seven top tips when intervening as a coach

- Any time we intervene, it needs to be useful for the players and delivered in a way that promotes understanding, giving them the confidence to try things, pushing against the boundaries of what they already know and are comfortable doing. It is not simply an opportunity to highlight players’ mistakes.

- Don’t intervene for the sake of it – be convinced you have something useful to contribute. Once you have set the players a new task, they will need time to breathe and sort things out, so leave them be to see what they already know and can do.

- Don’t dive in too quickly. Even if the odd mistake is being made here and there, watch for players putting things right on their own (that’s real-world learning). It’s your judgement call whether to jump in or not. Observe and think before you speak and take over. Give yourself time to breathe too.

- Make your interventions clear, quick and to the point.

- Don’t give too much at once. A good coach will challenge their players and explain things, but will do so at a rate that allows them to incorporate the new information into their developing expertise.

- Intervene in different ways, based on the needs of the group, unit or individual, and the given circumstances.

- Plan your potential interventions, or your options for them. If you have sufficiently planned for the aims and objectives of your session, you should know what you want to get out of it. You can, therefore, plan for different things you may see in your session, or on a matchday, and consider how you might want to intervene. Of course, the better you know your players, the better you will be able to do this. The aim, though, is not to be rigid with it. You can have intervention ideas in your back pocket, but the skill is knowing which ones to use, when to use them, and, most importantly, how to use them.

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Subscribe Today

Discover the simple way to become a more effective, more successful soccer coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Soccer Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Soccer Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use soccer drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of soccer coaching since we launched in 2007, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.